What do the world’s fastest drivers and our most cunning criminals have in common? A lot, it turns out.

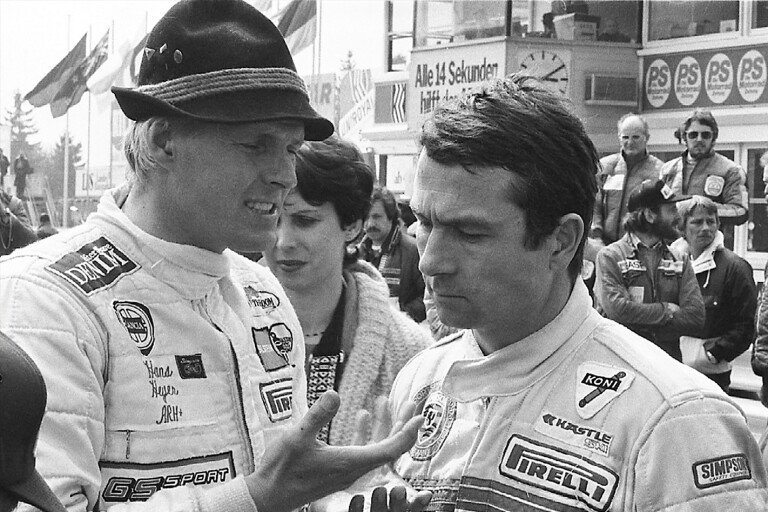

We’ll start with Hans Heyer, the only man to simultaneously fail to start, fail to finish, and be disqualified from the same race.

A prominent German touring car driver in the ’70s, Heyer decided to try his hand at F1 for his home grand prix at Hockenheim in ’77, but missed the cut-off to qualify for the race. That wasn’t going to cut it for ol’ Hans, and so with help from a couple of buddies volunteering as marshals he snuck onto the back of the grid and joined the grand prix.

Nine laps into Heyer’s F1 debut, a gear linkage on his Penske PC4 broke and he was forced to retire, at which point the officials clued in on his secret participation, disqualifying him on the spot. As a side note, Heyer also holds the record for most Le Mans starts without ever finishing – 12. Which brings us neatly to another dubious racer.

Jack Griffin was a moderately successful real estate broker from Texas who had a brief, if forgettable, racing career. He took part in just 17 races over three years, including a debut at the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1983, and participated in the 24 Hours of Le Mans the two following years. What makes Griffin’s participations so notable is the fact he didn’t have the licence required to compete in both of those events.

Two weeks prior to his professional debut, Griffin had never even sat in a proper racing car.

A four-day crash course at the famous Bondurant driving school gave Griffin the false sense of confidence he needed to take on Sebring, where he promptly crashed after completing 15 laps. You see, Griffin had a mate, M.L. Speer, a fellow Texan who did hold the required licences to compete, and a winning smile that stopped all inconvenient questions in their tracks. Speer had convinced Griffin to take part in the Sebring race, and followed it up with an invitation to spectate at Le Mans a year later.

It was there the pair heard that a French team, Bussi, needed a driver. A few more white lies later, and Griffin was set to compete against the likes of Klaus Ludwig, Vern Schuppan, and Stefan Johansson in the team’s Rondeau M382. A blown engine would mean Griffin’s Le Mans debut resulted in a DNF, but somehow this Texas real estate broker, who just 18 months earlier had never driven a racecar, managed to swindle his way onto the entry list.

Finally, we have the story of L.W. Wright, a veteran of 43 NASCAR Cup races from Nashville Tennessee looking for a ride in the 1982 race at Talledaga… or so he claimed. No one really investigated Mr Wright’s story as he was quick on the draw with cheques, laying them on the table to get what he needed to compete, including buying a car for $20,000.

Thing is, L.W. Wright didn’t exist.

It was a fake name dreamt up by a con man with zero racing experience who successfully swindled everyone he shook hands with. ‘Wright’ retired from the race 13 laps after it started, but by its conclusion was nowhere to be seen, and the cheques he’d used to pay his way onto the track bounced. Multiple arrest warrants were issued, but they remain unanswered to this day.

So, what do these three have to do with today’s motorsport elite?

Well, while Heyer, Griffin and Wright are the most egregious examples of bare-faced cheek, bulging egos and ethical flexibility in racing history, their tenacious approach isn’t entirely out of place.

The same mentality that pushed them to bend or outright ignore the rules is something every successful racing driver carries deep in their soul. Without it, a driver would never be able to compete at the upper echelons of the sport.

That same bravado is what allows Valtteri Bottas to fall asleep at night, confident in his own mind that he is a superior racing driver to Lewis Hamilton, and it’s what stops Fernando Alonso hanging up his helmet in graceful silence when a humble retirement calls his name. A recipe filled with a lack of remorse and no shame paired with a self-aggrandising mentality can just as easily make an elite-level racing driver as it can a grifter.

So, watch your wallet next time you’re at the track, eh?

COMMENTS