Five Australians have scored Formula 1 points. Six men have driven on the moon.

Of the Aussies to have succeeded in motorsport’s top echelon, Ricciardo and Webber spring easily to mind, and world champs Jones and Brabham need nothing in the way of introduction. The fifth usually foxes people. It’s Tim Schenken.

Even more intriguingly, he’s the only Aussie to have ever scored a factory Ferrari drive, albeit in sports cars not Formula 1.

So how did a kid who used to secretly borrow his mum’s Simca for races at Calder end up catching the eye of Enzo Ferrari?

“Because I was good enough,” he deadpans, before breaking into an impish grin.

“They approached me at the 1971 Monza Grand Prix. After the first practice, a woman came up and said ‘Would you come to the Ferrari garage?’ I thought it was a joke so I didn’t take much notice to be honest,” he smiles. “She came again the following day and I still thought someone was pulling a prank here. In the afternoon she returned, and she was really agitated. I thought maybe I’d better go.

I got into the Ferrari truck with Peter Schetty, who was the team manager at the time. He was so angry because Enzo Ferrari had come up the day before to meet me and had to stay overnight. I still had my overalls on, so I got straight into the car and went to a hotel in Lesmo. A bit unwittingly, I’d stood him up.”

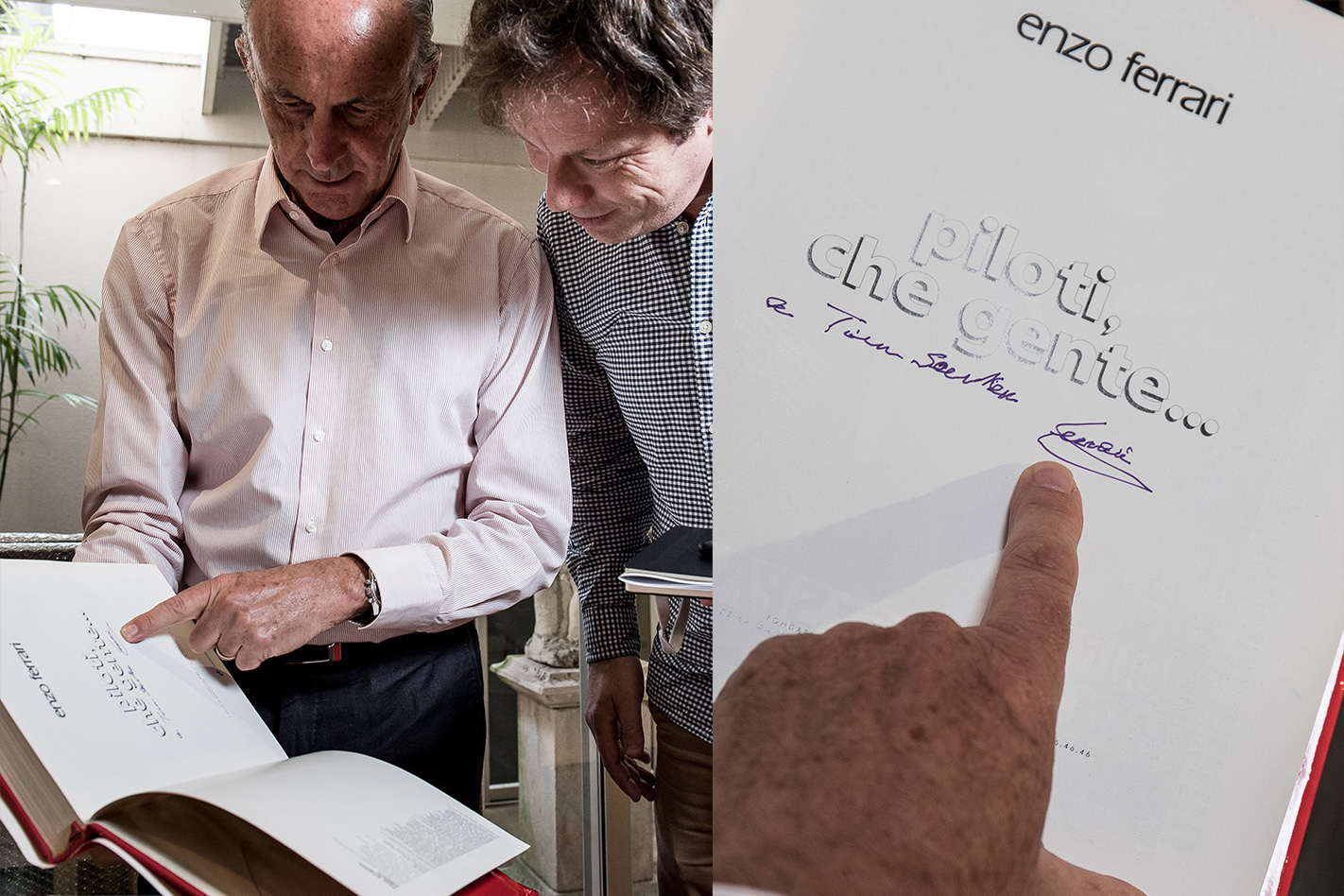

Clearly there were no hard feelings from the notoriously testy boss of the Scuderia. “In the back of the restaurant was Mr Ferrari, and he asked if I would drive for them.” Schenken signed for £2000 a race, with nine endurance events. “That was a lot of money back then. I don’t know what the other drivers were on but I knew that £7500 would buy a house in Maidenhead.”

“I met Mr Ferrari quite a few times. Ronnie and I won the first race of the year, the Buenos Aires 1000km, and afterwards we had ten or 12 trophies between us. When we got back to the team bus, I wondered what I was going to do with them all, so Peter Schetty suggested that we give three or four to Mr Ferrari. He loved it. After that, Ronnie and I were always welcomed there, and when we were testing at Fiorano or Monza, Mr Ferrari would always turn up and say hello.

“Ferrari is a great team to be with when they’re winning. When they’re losing, it’s a real struggle, as I found the following year. Matra came with a proper monocoque chassis and expertise from the aerospace industry and Ferrari hadn’t mastered how to build a monocoque. At that stage it was still a tube chassis. There was also the concern that the effort on sports cars would detract from what they were doing in Formula 1.

Fiercely pragmatic, Schenken cared little about the car he was in, just as long as it was the fastest. But it was clear Ferrari wasn’t just another racing team.

“I didn’t at the time, but when I look back now, I think it was fantastic what we did there at Ferrari. Fiorano had opened in 1971, so we’d take a car for testing and wander around the production line, but you didn’t appreciate it at the time,” he says. The unique nature of Ferrari’s manufacturing had its pluses and minuses. “Ferrari built everything themselves. It wasn’t like they were buying an engine from Cosworth. They built components to suit themselves. But that led to an atmosphere where when they’re winning, it’s the car; when they’re losing, it’s the driver.”

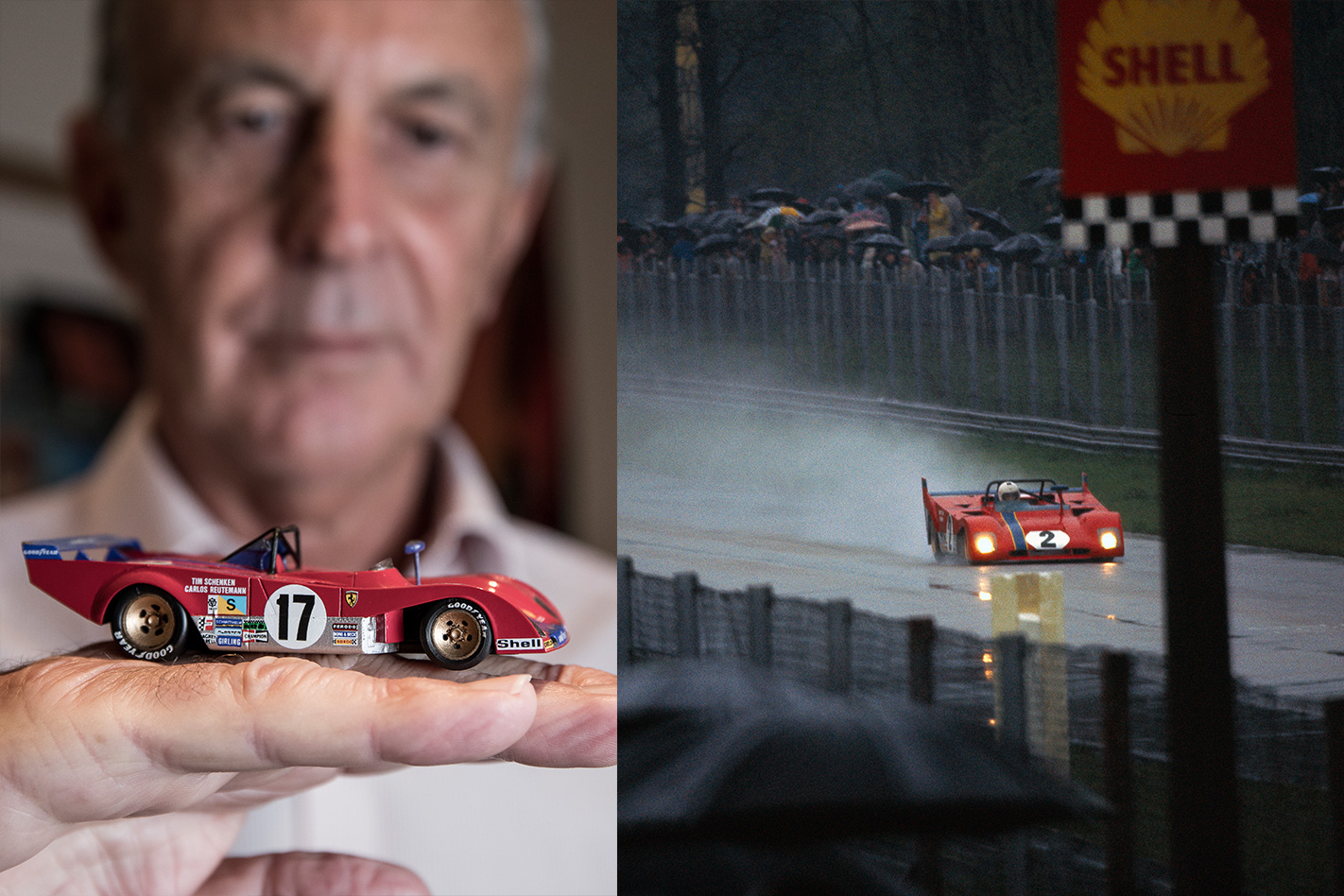

Ferrari wasn’t shy of wielding its huge reputational clout either. “At the 1000km of Monza in ’72 it was horrendous weather. In the warm up, two of our cars went off at the Parabolica. I was driving one. The cars came back with damaged bodywork just before the start of the race. Peter Schetty went to the organisers and told them to delay the start of the race or the Ferraris were going home, so they delayed the start.”

Even Maranello’s muscle could only go so far in mitigating the risks of the era. “At that time, I thought I was better off than Stirling Moss, Mike Hawthorn, Peter Collins and all those other drivers. We had seat belts, we had Bell helmets, we had fireproof overalls, we had a monocoque chassis, and we had bag tanks, so we were better off than they were. There were a lot of fatalities, but if you were worried about those things, you wouldn’t go racing”, says Schenken.

Near misses feature heavily in Schenken’s career, but once in a while, it all hit the fan and not always in the most predictable way.

Take Daytona in ’72.

“Ronnie Peterson and I were staying at the Holiday Inn opposite the track’s main entrance. We got sick and tired of the food there so we asked Mario Andretti where to go for dinner. He said there were some nice restaurants down in Daytona so we went down there and saw cars driving up and down the beach. We decided we’d have a go at that after dinner. I was the idiot driving, and Ronnie yelled, “Turn off here!”, so I swerved off the highway, up a ramp and into the air, finishing with a big slide onto the beach.

“It just so happened that a police car was driving past. The speed limit was 25mph, so the lights came on and he stopped us immediately. We had no ID at all, just cash. So it was off to the police station and we were taken down into the area where the cells are with the drunks, homeless people and criminals. It occurred to me that Ronnie wasn’t driving and that I was the one in trouble, so I asked if he could go back to the hotel and get some ID. Yes, that’s okay, they said.

“Ronnie being Ronnie, he lit the tyres up going out of the police station car park. He was angry. He took off and immediately there was an all-points bulletin to stop the car. They brought him back very sheepish and weren’t going to release him. “We decided to ring Peter Schetty to see if he could help. We didn’t want to do that because we shouldn’t have been out at midnight the night before the race.

We called him and he rang Bill France (the Daytona Speedway owner and NASCAR founder), who rang the police station and they got us out. The mechanics thought it was fantastic, Mario thought it was a huge laugh but Peter Schetty wasn’t very happy about it at all. We were leading the race the next day but I think we then had some gearbox problems. You only remember the wins!”

After hanging up his gloves, Schenken set up Tiga Racing Cars with Howard Ganley, a successful business that produced around 400 race cars in various formulae, giving drivers like Mike Thackwell, Stefan Johansson and Eddie Jordan an early break.

It’s a long way from cannibalising broken parts for an Austin A30 track mongrel, but then making your way as an Aussie at motorsport’s pointy end sometimes requires a little ingenuity.

As we walk out the door, there’s that grin again. “Daytona,” he chuckles, shaking his head. “You’re going to make me out to be a larrikin.”