RESEARCHERS at the University of New South Wales have discovered a cheap way of generating hydrogen from water, and their breakthrough could see hydrogen’s prospects as a long-term power source improve – and increase the likelihood it will power your car in the future.

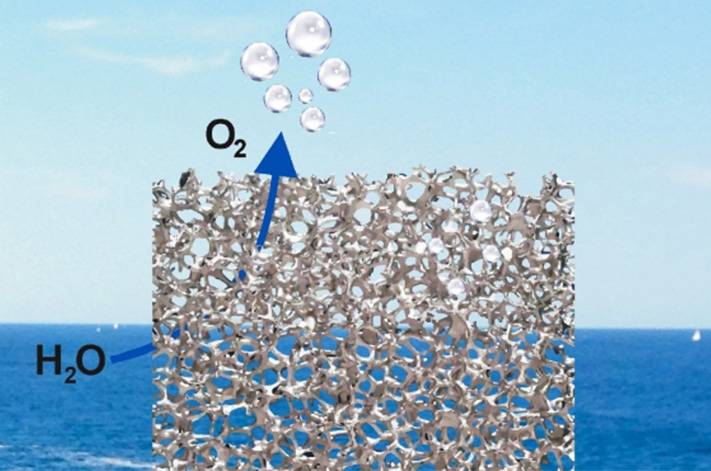

The study, led by UNSW associate professor Chuan Zhao, developed a method of creating ultra-thin metal catalysts out of iron, nickel and copper for splitting water into its component elements of hydrogen and oxygen.

Compared to present methods that require expensive rare metals like platinum and iridium, Professor Zhao claims his team’s technique is not only cheaper, but also yields more hydrogen.

When it comes to transportation, manufacturers have been split over whether to concentrate on pure electric vehicles or hydrogen as their future power source of choice. Energy density – the amount of energy that can be stored in a given mass – is key to determining which tech has a longer-term future, and while a tank of hydrogen can store more energy per kilo than a battery, it’s not without shortcomings.

Cost and infrastructure are the two main drawbacks. The need to deliver hydrogen at sufficiently high pressure and low temperature means a hydrogen fuelling station needs specialised equipment, while a battery-electric vehicle can be recharged from a regular household socket. Then there’s cost – electricity can be generated cheaply from renewable sources, while hydrogen must be derived using an expensive and energy-intensive process.

So while a car with a hydrogen tank, electric drive motors and a fuel cell to convert the hydrogen into electrical energy may be lighter than a car which has only a battery and drive motors, the cost and infrastructure required to make it viable is significant.

But when it comes to efficiency and scale, the process becomes more expensive. Precious metals that are already in tight supply – like platinum, iridium and ruthenium – currently make the best catalysts for generating hydrogen in industrial volumes, however they’re costly.

Zhao’s high-efficiency, low-cost cracking process may not solve the infrastructure issue, but by bringing the expense of hydrogen generation down it goes some way to improving hydrogen’s odds of becoming the mainstream fuel of the future.

“Splitting water usually requires two different catalysts, but our catalyst can drive both of the reactions required to separate water into its two constituents, oxygen and hydrogen,” Professor Zhao said.

“Compared to other water-splitting electro-catalysts reported to date, our catalyst is also among the most efficient.”

But what’s the current state of play? Manufacturers have been bullish on hydrogen in the past, but as battery technology has improved and the cost of battery storage has dropped, so too has the willingness of carmakers to invest in hydrogen fuel cells.

BMW is a high-profile example. The German carmaker, which has dabbled with experimental hydro-gen-burning internal combustion engines and more sophisticated hydrogen fuel cells, has gone cold on fuel-cell tech. Speaking at the launch of the 530e plug-in hybrid, the head of BMW’s i division Alexander Kotouc said “the future is fully electric”.

“We all know about the situation when it comes to infrastructure for electric cars. If you now look into the infrastructure for fuel cell or hydrogen, it’s at a much lower level at the moment,” Kotouc said.

“So the technology is perfectly fine, we are looking into that, but it doesn’t make sense to offer it on a mass scale to consumers if they don’t have anywhere to [refuel] the cars.”

There are exceptions. Honda, one of few manufacturers to offer a fuel cell vehicle to the public in the form of the FCX Clarity, remains committed to a hydrogen future. Same goes with Honda’s compatriot, Toyota, which launched its Mirai fuel cell car in 2015.

Hyundai has has been involved with fuel cell powertrains for a while now, with a hydrogen-huffing ix35 being the first production car to be born from the Korean carmaker’s alternative fuel program.

Meanwhile even Volkswagen, which has announced an aggressive strategy to launch 30 pure electric cars by 2025, isn’t giving up on hydrogen fuel cells. However the German carmaker will likely make hydrogen the preserve of its luxury offshoot Audi, with fuel cell powered concepts like the H-Tron quattro an early signal of what’s to come.

Mercedes-Benz is another big backer of pure electric tech, but has also announced that a hydrogen fuel cell GLC-class will arrive next year – also toting a plug-in capability to allow it to run even when hydrogen filling stations are scarce.