If knowledge is power, ignorance is unlikely to produce winners.

Yet the competition cars Mercedes-Benz brought to Silverstone to celebrate the company’s 125 years in motorsport earlier this year told a very different story.

Looking closely at the machinery on show, both in the exhibition halls of the huge Silverstone Wing event centre above pit lane and on the track itself, there was plenty of ignorance to be seen. Although the collection of cars assembled at Silverstone were winners one and all, many of them spoke with silent eloquence of how much their creators did not know.

Naturally enough, examples were easiest to find among the oldest exhibits. Mercedes-Benz has existed since 1926, when Gottlieb Daimler’s Mercedes brand merged with Karl Benz’s company. Both took part in the 1894 Paris to Rouen event widely acknowledged as the world’s first car competition.

The Benz finished 14th, but the Panhard and Levassor and Peugeot cars that shared the big prize money on offer from magazine Le Petit Journal were powered by licence-made Daimler engines. Two were on show at Silverstone. This winner is a narrow-angle V-twin of around 1.6-litres. Maximum output? Almost 3kW.

What caught my eye was the ignition system, which is basically a small brass stove at the top of the engine. Inside are two manually adjustable burners. These heat short tubes with closed ends that pass through the cylinder walls and into the combustion chamber.

This ‘hot tube’ ignition apparatus looks utterly nuts to modern eyes. But Daimler and his top engineer Wilhelm Maybach didn’t know that Robert Bosch would electrify petrol-burning internal combustion engine ignition in a literal sense only a few years later, patenting the high-voltage spark plug and magneto in 1902.

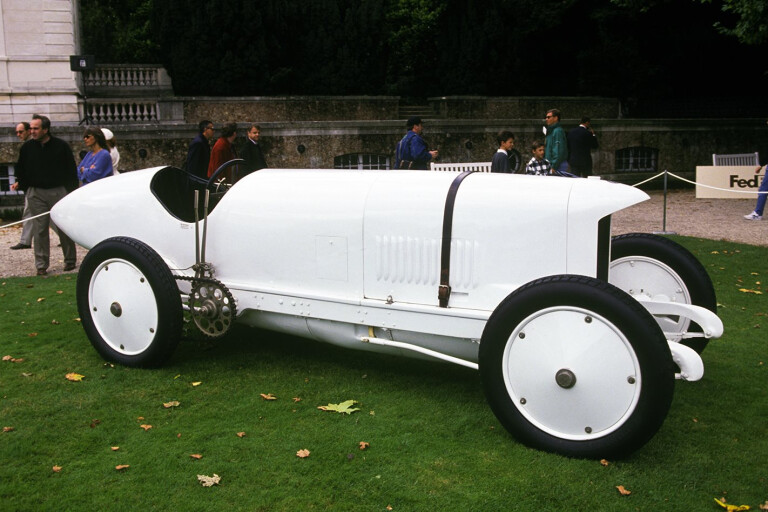

Chuffing through four slash-cut stub exhausts, the 1909 ‘Blitzen’ Benz is an awesome artefact. Seeing it run at Silverstone was a thrill, even if this white-painted elephant was brought to life only briefly. For a time, this was the fastest vehicle in the world. It was eight years before another car, or motorcycle, aircraft or boat, could beat its record 228km/h over a mile at Daytona Beach in 1911. It took a 21.5-litre engine, specially designed for the job and equipped with spark ignition, to produce the 150kW or so needed to reach such speed.

The engine is massive, because that’s the only way Benz’s best boffins could think of to make big power. They weren’t to know that advances in metallurgy were coming that would make possible compact, high-revving engines that roared and screamed instead of huffing like the Blitzen Benz, while producing way more power.

The Silver Arrows of Mercedes-Benz’s golden age in motorsport are lovely cars, but these pre- and post-WWII racers display scant knowledge of safety. The theory – and it was never anything more – was that your chances of survival were better if you were thrown out of the car. By this logic, seatbelts were killers, not lifesavers. So they weren’t fitted...

Even in the current age of the F1 driver halo, there’s still much to be learned. Walking along the chronologically ordered row of Mercedes-AMG Petronas F1 cars trucked to Silverstone was fascinating. Year by year through the hybrid era that began in 2014, the increasing complexity of their front wing designs is a sure sign of the team’s improving understanding of aerodynamics. In essence, there’s no great difference between the aero team who designed the front wing of the winning 2018 car and the Daimler engineers who more than a century ago produced an ignition system that needed to be lit with a match.

How much more will we know tomorrow than we do today? No-one can say for sure. But winners always will be those who make the most of what they have to work with in the here and now.

COMMENTS