There are two ways you can go in this world: you can stick with what you’ve got, tweak it and improve it over time or simply chuck the lot out and stump up for a brand new concept.

This article was first published in MOTOR’s June 2006 issue.

Ford was content to play out the late 1990s by upgrading the 5.0-litre Windsor in a series of steps that took the old girl from pretty ordinary to fairly damn handy. The EL model XR8 was the first to benefit from an improvement to the Windsor’s breathing capacity, followed by the later versions of the AU XR8, which got firstly a 200kW tune and finally a 220kW set-up complete with alloy heads and roller rockers.

With 5.4 litres of displacement, the new motor was on the pace but even more significantly, while the Gen III stuck with pushrods and two valves per pot, the new Ford mill ran to double-overhead camshafts and four-valves-per-cylinder. But while Holden’s Gen III was straight from the GM Powertrain catalogue, nothing in Henry’s arsenal here or overseas seemed right for the job of powering the next generation of XR8s.

See, the DOHC 4.6-litre Mustang mill was never going to give the torque Aussie XR8 buyers were looking for, and the 5.4-litre engine wasn’t available in quad-cam form. The solution was to take the 5.4’s bottom end and mate it to the DOHC heads of the Mustang motor.

So that, in a nutshell is how we arrived at the 5.4-litre XR8 V8 but convincing the Yanks it would work was just the start. Another major drama was that the mill was so damn big and tall that it barely fitted under the BA Falcon’s lid.

The other problem was that being a DOHC engine with big, fat heads, the not insubstantial weight was carried high. And anybody will tell you that a high centre of gravity is not good for handling.

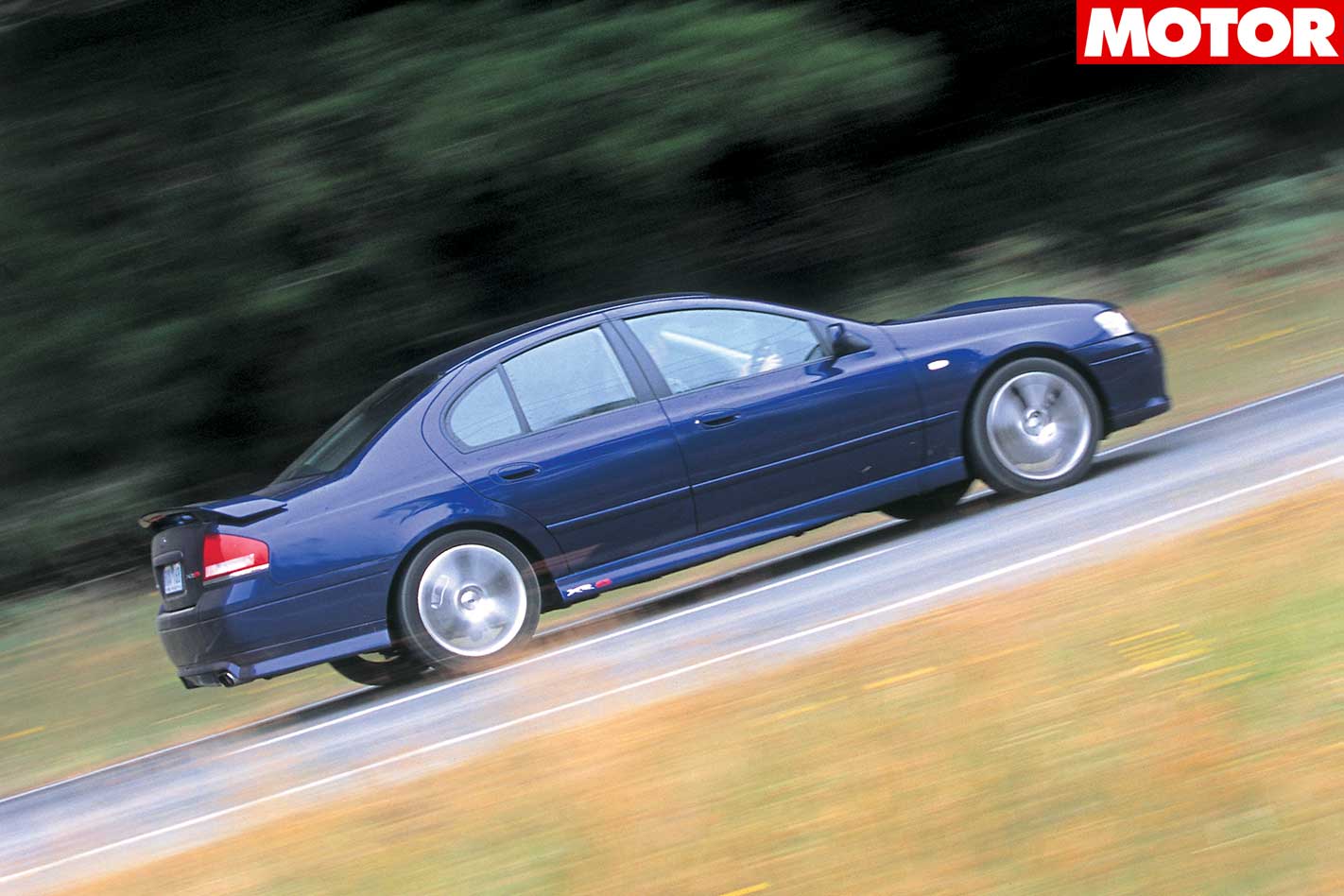

The rest of the XR8 package was a bit more familiar with the usual body kit and sportier interior trim as well as firmer suspension settings and 18-inch alloys. Throw in bigger brakes and a slippery diff and you had a pretty complete deal when it comes to hot-rod locals that are also able to seat five big bums and tow a dirty big fishing boat. So how’d it all go, then?

And it wouldn’t have been so bad had the lighter-in-the-nose XR6 Turbo not been selling alongside the XR8, just to ram home the V8’s lack of agility.

But get your head around that, and there was a fair bit to like. For a start, the XR8 was a more relaxed cruiser than the Commodore SS, with better ride and a quieter end result.

The optional four-speed automatic is far and away the most popular choice and, to be perfectly honest, makes the most sense. It’s a good tranny and it works well with the big eight because the torque-converter masks a little of the low-speed lack of urge. If it has to be a manual, you’ll be faced with the old Tremec five-cogger which is strong but clumsy and clunky to shift.

While the new V8 was certainly high-tech, it simply didn’t translate to the street. The redline of 5500rpm seemed a bit odd in light of the specification but the conventional flip-side of a slugger engine – mega low-end torque – wasn’t there, either. Then again, no production Windsor ever cracked on like the DOHC Henry from about 4000rpm onwards. Problem was, it was all over by 5500.

As it’s an engine-out job just to fit extractors, it’s not easy or cheap matter to screw more out of the 5.4.The long-stroke design also means that swapping to bigger cams and revving it harder isn’t really an option. Aside from a piggy-back computer that will really only maximise what you’ve already got, the most viable way to go harder in an XR8 is forced induction. Even then a turbo just won’t fit.

That leaves you with a belt-driven supercharger, but it’s not going to be a cheap one by the time you’ve got it sorted. Tuning, it seems, is just one more field of endeavour where the turbo six has got big bro kicked to bits.

What we said? “Post-apex oversteer is readily available via the right clog and it’s so benign and predictable that big, full-oppy-lock slides are yours for the taking. And the new Henry lump easily manages to tag its rev limiter, set just beyond 5500rpm, with consummate ease.” – David Morley, March 2003

What else could you buy? For the same money you’d need to sign away for a BA XR8, you could get your hands on a VY Commodore SS – which of course is the obvious answer. If you’re prepared to think outside the box and go older, try a BMW 5-Series or Audi A6 from the mid 1990s.