I had one constant travel companion during my four-month, 25,000 kilometre journey across the north-west of Australia.

This feature was originally published in 4×4 Australia’s May 2009 issue

This one companion shared every experience over thousand-kilometre stretches of bitumen as we kicked up dust along unpaved red roads and waded together across wide, deep rivers. My constant companion over these long, but never lonely roads was my Troopie.

The Troopie was a bit of a head-turner in Melbourne – the huge, white, glistening truck somewhat out of place in suburban city streets. I think the Troopie was as keen as I was to get packed with everything I might need for four months of campfire-cooking and swag-sleeping, and just get out there and hit the open road.

My Troopie wasn’t my only travel buddy during four months on the road – every so often we were joined by friends to share sections of the adventure.

The basic itinerary for the trip was up through the centre to Arnhem Land and Darwin, then along the Gibb River Road and the Mitchell Plateau on the way to Broome, before returning south via the Tanami Track.

Bo was our first passenger. He jumped on board in the depth of a Melbourne winter, ready for the long drive north. I picked him up straight from his office on a Tuesday afternoon and it took us a couple of days to shake the city from our psyche as we trundled along highways, dreaming of the desert.

It was so cold over the first few nights that we ended up staying in sleepy ’60s roadside motels instead of camping out. Finally on our third night, just north of Coober Pedy, we set up camp and lit a campfire under a dramatic wide-sky sunset. It was our first real sense that the road trip had begun.

Earlier that day we’d spotted an emu dashing through the scrub and the dirt by the road was gradually becoming a stronger shade of red – we had finally left the city behind.

Bo had never been to the Red Centre before so we made a spur-of-the-moment decision to turn left at the Lasseter Highway for an 800km detour into Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. Four hundred kilometres to the Rock felt like a short sprint before breakfast under our new, recalibrated, sense of distance.

The detour was worth every centimetre. We were entranced by the mystical quality that floats in the air around Uluru and Kata Tjuta (the Olgas). These rock forms are so domineering they even influence the shape of the cloud patterns above. They are magnificent from afar and mesmerising up close. We walked the 10km around the base of Uluru and enjoyed the distinctive personalities portrayed by different sections of the rock.

The 800km Uluru detour threw us into an entirely different head space; we both felt the city was light years behind us, and that we’d been travelling for many months. It was a transforming mind-shift after less than a week on the road.

Returning to the Stuart Highway was daunting after emerging from the cocoon of the national park – our next significant point on the map wasn’t until Katherine, almost 1500km ahead. Luckily we quickly returned to the bitumen groove and had fun testing the might of the Troopie’s V8 turbo-diesel engine along the empty highway stretches. This part of the journey was dotted with impromptu visits to fruit farms for wine-tastings and homemade ice-creams.

When we finally arrived in Katherine our first task was an administrative one. You need a permit from the Northern Land Council to travel along the Central Arnhem Highway and Bo and I had applied for these separately a few weeks before we left.

Upon our arrival at the NLC Katherine office, the woman went away to her filing cabinet and came back with one form which she handed to Bo and pointed for him to sign. I waited patiently for my form before eventually asking for it. To Bo’s amusement, and my mock horror, the woman in the office replied: “You don’t need a form, you’re just the passenger”.

With our NLC “driver” form in hand, the Troopie, Bo and I were finally ready to veer off the bitumen and play in the red dusty gravel.

We loved every moment of our off-roading adventure up into Arnhem Land. Our travels took us through a wild pandanus forest, past giant anthills, across fresh water buffalo tracks and even across a bloated-belly buffalo carcass by the roadside. At night we fell asleep to the wail of distant dingoes. Most of our time in Arnhem Land was spent at the Garma Festival (see right) but we still managed to explore some of the pristine north Australian beaches and hidden waterfalls during our visit.

After a return trip back down the Central Arnhem Highway, I dropped Bo off in Darwin in time for his flight home. My next passenger, Natasha, jumped on board to join the Troopie and I along the Gibb River Road headed for Broome.

This 3000km leg included a detour north of the Gibb River Road, up through the Mitchell Plateau, and included some of the roughest roads of the entire trip. The sense of isolation in this part of the country was intensified by the complete lack of mobile phone range – which also provided the opportunity to completely disconnect from world news and gossip from back home.

We discovered that two women and a Troopie travelling through this remote northern plateau was quite a novelty, and Tash and I were generally met with a combination of incredulous disbelief, condescension or concern.

One man asked: “Why are you girls travelling alone?” Simple answer: “We’re not travelling alone, we’re travelling together.”

When we were at Mitchell Falls we exchanged travel tales and itineraries with some other off-roaders. Half an hour later, from our shady perch by the swimming hole, we overheard a man call out to another traveller: “Have you heard there are two lasses travelling alone in a LandCruiser?” Later in the week a couple asked us: “Do you girls know how to change a tyre?”

We had not only rehearsed our 4X4 tyre-changing skills before we left, we also had a boot-full of gear that would have impressed any girl scout. Our emergency supplies included two spare tyres (the bare minimum), two jerry cans of diesel fuel, an air compressor, a satellite phone, an EPIRB, 80 litres of water and at least two weeks’ worth of food.

Despite all that concern from other travellers we’d encountered, Tash and I survived the river crossings, rugged roads, bush-camping, map-reading and long hikes into magical freshwater swimming holes with only one terrifying moment.

That moment occurred at about 1am when I woke up on a moonless night and sensed a hulking shadow above us. Tash was ripped from her dreams to the sound of my panicked words – “What is THAT?” – as my half-dreaming eyes saw the shadow transform into what looked like a giant bull.

The two of us scrambled from our swags and ran behind the Troopie to put a line of defence between us and our tormentor. Our spotlight revealed the threat to be a wild cow (she did have small horns) who was dining on the leafy branches of the tree that we had chosen to roll our swags under.

The cow’s meal was cut short when she finally noticed the spotlight we were staring her down with and she scrambled away in fear, in much the same way Tash and I had done minutes earlier. We returned to our swags and spent the next few hours talking and watching shooting stars – waiting for the midnight adrenaline to fade.

Tash and I had mixed feelings as we were pulling into Broome at the end of our remote two-week adventure. We were excited about the prospect of a shower (the first one in almost 10 days) and a swim in non-croc-infested salt water, and as much as we hated to admit it, we were hankering for a freshly brewed coffee. But this also meant a return to the world of mobile phones, internet, street-lighting, footpaths and other signs of civilisation we had enjoyed living without.

Admittedly, it didn’t take us long to ease into Cable Beach sunsets and restaurant meals. Tash even splashed out during an extended shopping spree through Broome’s China Town before flying back to Darwin.

After Tash left, the Troopie was my sole travel companion for the next phase of the journey, which involved research trips between Fitzroy Crossing and Broome, and across other parts of the Kimberley.

I was based in the Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture Centre office for a month in Fitzroy Crossing and during this time shared a house with two guys who worked in town – Simon, who works with Indigenous youth through an organisation called the Yiriman Project, and Andre, who works at the art centre, Mangkaja.

This was a very social time for my Troopie who found itself in familiar company, because both my housemates drove identical vehicles. There wasn’t much room left over in our front yard when our three giant TroopCarriers were all lined up in a row.

The three Troopies had a team adventure in late November, the day the season’s first storms came through without warning. Simon was out fishing on the Fitzroy River and ended up getting bogged in fine, black sand. The rising-river rescue mission took two Troopies and four hours to complete and ended in a bountiful midnight fishing expedition.

The final leg of my four-month journey was from Fitzroy Crossing back home to Melbourne via the 1000km Tanami Track, with my housemate Simon along for the ride. The Tanami Road is sometimes closed due to heavy rain and we were on standby right up until the day we left as to whether we’d have to take the alternative route via Kununurra and Katherine, adding 1000km to the trip. Sections of the Tanami Road had been closed the week before our departure, but the rainfall cleared just in time to get us through.

When the roads are open, early December is a fantastic time of year to drive through this part of the world – the skies are painted with dramatic rain clouds and the fresh, green sprouting scrub provides a spectacular contrast to the dark, red desert. And best of all, you have the whole place to yourself.

Simon and I spent the first night of our homeward journey camped out at Wolfe Creek Crater without another person around. The next morning we spent two hours hiking into the deep gash left by an ancient meteorite and we inhaled the view from the top rim of the crater out across hundreds of kilometres of empty desert lands – giving us a strong sense of the vastness of this desert we were crossing by car.

The Tanami Road was in much better condition than we’d expected – almost to the point of anticlimax after all the warnings we’d been given in the lead up to our departure. The only rough section of the track was between Balgo and the Rabbit Flat Roadhouse.

We spent our second night along the Tanami staying with friends of friends in the Aboriginal community Yuendumu. We stayed up until midnight enjoying the company of our hosts and the next day had a long chat with Francis Kelly – the star of the ABC series Bush Mechanic – about his many years of Australia-wide travel and his recent brush with celebrity following the success of his show.

From Yuendumu it was a quick trip back to Alice Springs and then a 2500km barrel along bitumen south back to the city. The turning point of this trip, four months later, was once again close to Coober Pedy, where a frosty bite came back into the air – something I hadn’t experienced for many months in Australia’s wild north-west desert country.

The drive came to an end more quickly than we wanted it to. Suddenly there we were: on the outskirts of Melbourne.

The Troopie was whisked straight in for a thorough car detail – all evidence of red dust and desert adventure scrubbed clean. It wasn’t until I picked the car up, and saw it all glistening white and sparkling again, that I had a true sense of the journey being over.

I was almost right was back to where I started: driving around in a clean white truck in the city. Only this time, the purr of the Troopie’s TDV8 engine sparked vivid memories – setting my mind whirring with the recollection of experiences – of many months of adventure with this constant companion along one very long road.

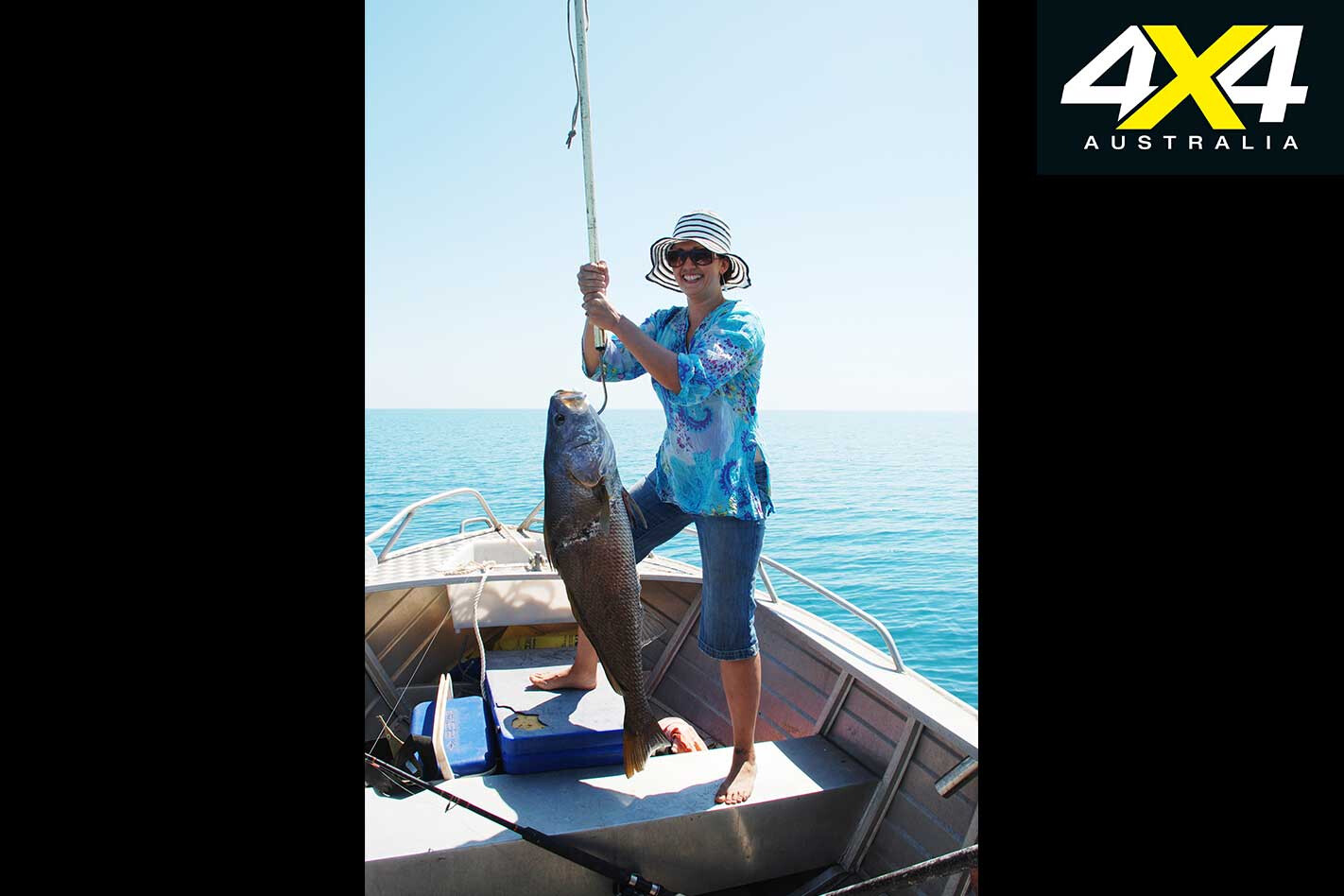

Fishing McGowan

McGowans Island Beach is one of the most remote mainland beaches on the planet. This tropical paradise is at the top of Mitchell Plateau, north of Kalumburu – a township originally established by a Catholic Mission more than 100 years ago.

Natasha and I pulled up our swags under two palm trees and made ourselves right at home at our ocean-view campsite.

The fishing up here is spectacular and we spent half a day out on the water with some local fishermen. Within the first half hour, Tash had reeled in a 50 pound West Australian dhufish.

Not long afterwards, I began my own 15-minute battle to pull in an even bigger dhufish, which we unhooked at the surface because we had more than enough fish to eat. We also caught sea perch and threw back a dozen javelin fish, reef sharks and queenfish.

Garma Festival

The Garma Festival is hosted in August each year by the Yothu Yindi Foundation in a site close to Nhulunbuy in Arnhem Land. It’s a celebration of the Yolngu culture and presents a mix of art, dance, culture and workshops. The Yolngu word “garma” means “both-ways learning” and the event brings together communities across Arnhem Land and guests from around the globe.

Each year an academic forum, co-ordinated by Charles Darwin University, focusses on a specific topic. Recent themes have been Indigenous education, health, culture and arts. Regular guests of the forum include esteemed Melbourne University academic Marcia Langton and ABC Latenight Live presenter Philip Adams. Former Australian of the Year Galarrwuy Yunupingu (brother of Mandawuy, lead singer of Yothu Yindi) is the face of the festival.

In 2008 Garma celebrated its 10th anniversary. It brings together some of Australia’s top musicians, but the central focus is the Bunggul, a performance of traditional dance and story-telling.

Canyon to Rock

By complete coincidence, my unplanned visit to Uluru happened to fall on the weekend that my dad arrived at The Rock after an eight-day adventure trek from Kings Canyon.

My father, Geoffrey Knight, and well-known adventurer John Muir had just walked 160km across the desert and salt plains on a direct path from Kings Canyon to Uluru. They had each pulled a trailer carrying 90kg of supplies – including less than five litres of drinking water per day – and all the food they would need to sustain them over the desolate trek.

It was a Saturday morning when the pair were scheduled to arrive at The Rock. Instead of waiting for them in the carpark, I began to walk around the base of Uluru in the direction they were meant to be arriving.

After about two kilometres of walking, and just before I decided to turn back to the carpark, I noticed two men in the distance with wild beards and wide-brimmed hats; they looked like travellers from Central Asia or pioneers from a different era. Within 20 minutes, back at the designated arrival spot, I discovered these two gentlemen were, in fact, the very same ones I had been looking for.

They looked exhausted and bedraggled and Dad, who has climbed a number of the world’s highest mountain peaks including Mt Vincent in Antarctica, Denali (Mt McKinley) in Alaska and Aconcagua in the Chilean Andes, said the 160km trek was the most difficult thing he had ever done. It was also, he said, spectacular to finally touch the base of the rock after having spent so many days watching it loom in the distance.

The Dog Fence

The Dog Fence is a stretch of wire and wood that runs for more than 5000km from Surfers Paradise right across the country to the Great Australian Bight, west of Adelaide.

Pioneers started building the fence in 1880 and it took five years to finish. Its purpose was to keep dingoes out of the sheep country in the south-east of the continent. It captured the imagination of Sydney Morning Herald journalist James Woodford, who wrote a book called The Dog Fence (Text Publishing) about its construction and maintenance and the psyche of outback Australians in their battle against the wilderness.

A visit along the edge of the fence that runs east of the Stuart Highway takes you through the Breakaways. This surreal landscape, with its moon plains and multi-coloured flat-topped mesas, was once part of the Flinders Ranges, located much further south, but broke away from the range more than 60 million years ago.

As the sunrise or sunset light infuses golden hues into these sandstone formations, it is easy to be overwhelmed by this timeless and ancient landscape.