WHICHEVER of Australia’s eight capital cities you choose as a starting point, travelling to the centre of Australia means thousands of broken white lines, millions of kamikaze insects and enough dust to induce some serious respiratory issues.

If you strategically positioned yourself in Europe, you could cross four or five countries in the same distance it takes you to get from our glistening coastline to our parched red centre, albeit without the toll roads, arrogant French drivers and roadside caffeine hits.

But where exactly is the centre of Australia? That apparently simple process of defining the dead centre of the country could easily lead to some overturned bar stools or spilt amber nectar.

Sure, most travellers will head to Lambert Centre, the result of a 1988 bicentennial project to locate the gravitational centre of our 7,692,024 square kilometres. It even has its own road, complete with clear, concise signs to easily locate it (at least once you’ve covered the first few thousand kays getting to that point). The promise of a snazzy plaque and scale replica of the flagpole on top of Parliament House make it an easy win for adventurers looking to bulk up their Instagram or old-fashioned photo albums.

However, prior to 1988, Lambert Centre wasn’t even on the map. Literally. The centre was somewhere else; or, to be more precise, four places else.

Some quick Googling reveals there are at least five methods that have been used to calculate the centre of Australia over more than a century. All fall in the Northern Territory but are spread over a distance larger than Tasmania, which sort of reinforces that the whole find-the-centre thing isn’t an exact science. They all look pretty close when thumbing through a map, but conceivably a day or more apart once some challenging outback roads enter the equation.

The enormity of the task ahead hits somewhere pounding north along the Stuart Highway, with kangaroos risking their lives for some roadside greenery that is a rare sight in one of the most barren parts of the country. Sure, getting to the Red Centre that consumes a sizeable swathe of Australia’s interior is a big task, but finding the location of five dead centres is next level.

Our weapon of choice is the Mercedes-Benz X-Class ute. Our top-of-the-range X250d tops-out well into $70,000, adding some (real) leather and 19-inch wheels to the already impressive luxury tally. For the 110km/h – and, later, 130km/h – run up the highway it’s a comfy machine, its noise suppression impressive over longer stints. That’s a bigger deal than it may seem, with the lack of white noise a bonus for the many hours spent with cruise control engaged.

The 2.3-litre twin-turbo engine is also impressively frugal, sipping close to its claimed 7.9 litres per 100km average over the faster sections. It means we can eke almost 1000km from its 80-litre tank, at least when driving it gently. That the fuel light insists on blinking to life 200km before we’re likely to grind to a halt is a tad OTT. Still, at least it allows time for planning ahead.

First stop is Alice Springs, the closest thing we’ve got to a sizeable town in the centre of Australia. With a population approaching 30,000 it’s officially way smaller than the likes of Bendigo, Bathurst, Mildura, Tamworth and Albany – towns that all rate far less of a mention on evening weather reports.

Then again, that’s the advantage of being out on your own. As the most populous place anywhere near the centre of the country, the Alice is a big deal.

After a refuel and refresh we’re heading north, briefly continuing the northerly Stuart run before joining the head of the Tanami Track, which, if you take it along its corrugated length, gets you to the bottom of the Kimberley. We’re not going nearly that far, limited to the first 150-odd kilometres, all of which is surfaced.

The occasional road train makes the slithering, lumpy blacktop appear narrower, forcing a Bridgestone into the dirt to save wing mirrors (and more). The relative steering accuracy and on-road nous of the X-Class is a plus. But it’s an easy drive, at least until we locate our turnoff towards Glen Helen, a public road that doesn’t encroach on Aboriginal land (you can also arrive farther south via the West MacDonnell Ranges; although, check with the Central Land Council as to whether you need a permit).

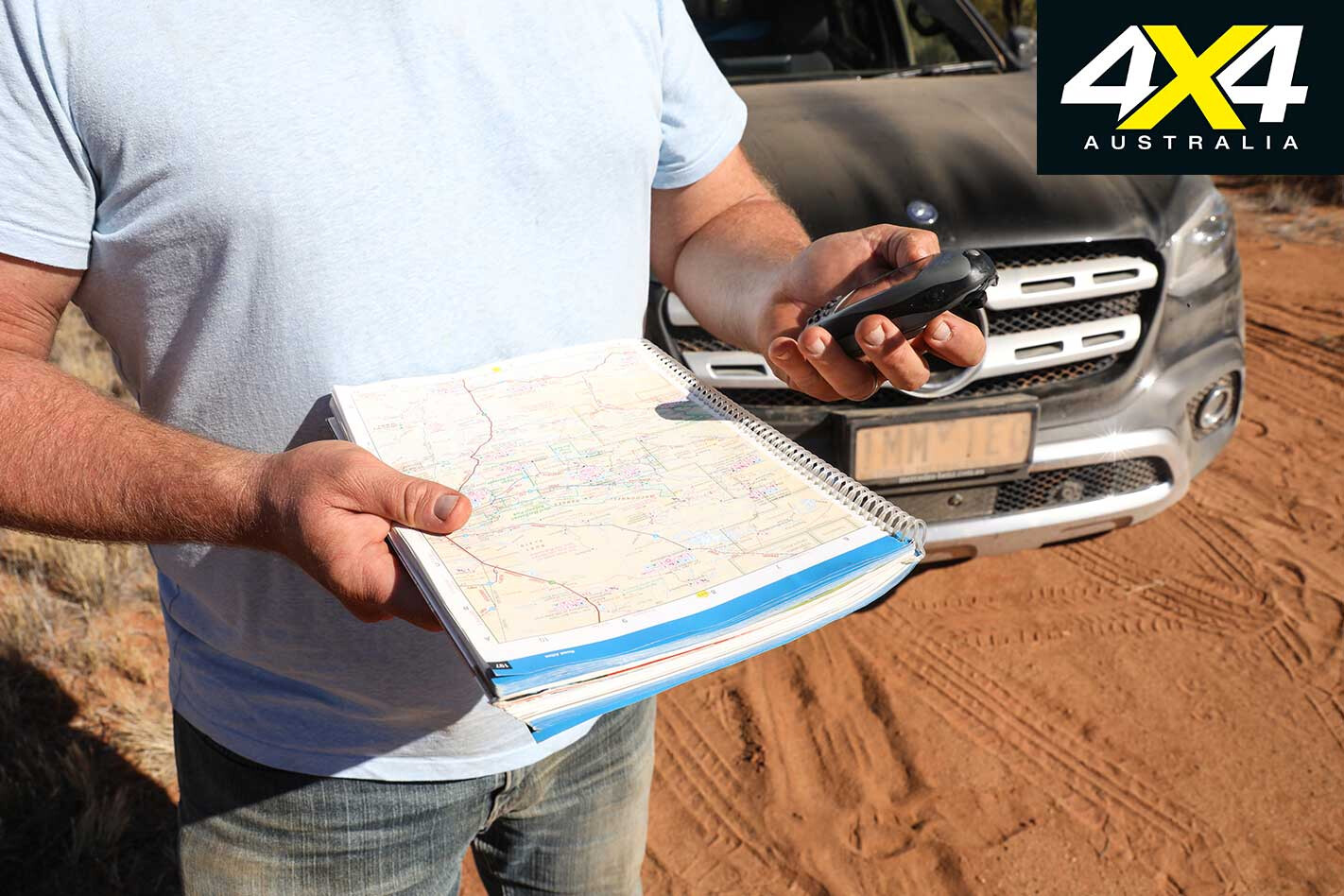

The transition to wide, red dirt surface doesn’t slow speeds much from the main road, our portable GPS reaffirming we’re heading in the right direction towards two of the centres. The ones we’re aiming at are the farthest point from the coastline and the gravity method, each of which is about 10km apart as the crow flies.

While we’re relying purely on GPS and paper maps, before we even left the sanctity of mobile range we spent many hours perusing Google Maps to get a feel for the type of terrain we were heading towards… and to get a better understanding of where we needed to go. None of which can prepare you for a decent puncture, like the one we copped on the relatively high-speed dirt.

It’s generally smooth and flat, but something long and sharp managed to pierce the 19-inch tyre, now beyond repair. Fortunately the full-size spare beneath the tray ensures no lost progress.

Both our first centres are on leasehold land, part of Derwent Station. If you’re any chance of making it to these centres you’ll need to touch base with them first to arrange access. It’s not guaranteed, especially when mustering is underway, but it at least tempers expectations before you start driving down dead-ends. Besides, it’s easy to take a wrong turn or get lured by the direction the GPS is pointing in – and you’ll do better with directions from the managers of the station.

Don’t expect a welcoming party when your GPS pings to alert you you’re on the spot, though. There’s no fanfare or markers, just the satisfaction you’ve reached two of the centres.

From there it’s backtracking through Alice Springs before heading south on the Stuart Highway in search of the median point. The journey from Alice is an easy 80km run; although, it’s the last couple of kilometres that prove a challenge.

Punching in the GPS coordinates all but confirms these locations were rounded to the nearest minute of latitude and longitude. After all, three of the five centre points don’t nominate seconds, only degrees and minutes. It’s either a massive coincidence or an indication of the accuracy of those earlier centre locations. We’re guessing the latter.

Assuming some rounding has occurred, the actual location could be approximately 700 metres in any direction from the one we’re chasing, which potentially makes the median point more achievable.

Our GPS is suggesting it’s about 2.7km off the main road, but with a locked station gate in front of us, we’re going no farther. Besides, best estimates put it somewhere on top of a hill, and satellite images aren’t giving much away in terms of access roads. So this is as close as we’re going.

Back on the Stuart heading south and it’s another 230km towards the southernmost centre point, one determined in 1965 and enlisted for surveying duty from 1966. Homing in on the location it’s clear it’ll be somewhere close to the main road, pretty much at the entrance to Mt Cavenagh Station.

From those gates a keen eye will spot the cairn on top of a small hill, about one kilometre off the Stuart Highway. Bring your binoculars and you’ll get a better view.

However, we want to get closer, so we head towards the homestead not far along a dirt road, meeting some station hands along the way, more than eager to show off their piece of Aussie history. They’re just as interested in a ute sporting a Mercedes-Benz badge, less impressed to hear it’s got Nissan power.

Anyone visiting Mt Cavenagh should call the station ahead of time to ask for permission, and be prepared to fall just short. You’ll only be driving to the base of the hill, a rocky outcrop that no car will be climbing – not even a modified Wrangler. Keen hikers can make a path to the top, though.

For almost 20 years the small collection of rocks with a nondescript plaque attached was used to survey points all over the country. It’s a point of significance largely lost on many of the locals, some of which have no idea it is even there, let alone what it was originally used for.

Of course, any journey to the centre of the country must incorporate the most famous of all, Lambert Centre, the last point on our centre-run. It’s a 20km drive north to Kulgera before heading east towards Finke.

It’s an easy 130km cruise along occasionally choppy dirt to the well-marked turnoff, at which point things get more interesting. Some soft sand and dips on the various tracks that all charge north to the geographic centre of the country will occasionally keep you on your toes.

We engage the part-time four-wheel drive system of the X250d for added traction, its high range comfortably dealing with the easy conditions. Arriving to the clearing at the centre you at least know you’re there, with the miniature flagpole mimicking that on top of our Parliament House some 2100km to the south-east.

If you’re the only ones around, the sprawling campsite isn’t a bad place to set up a tent for the night, with some drop dunnies off to one side.

From there you can be guaranteed a decent drive home, safe in the knowledge you’ve at some point (hopefully) hit the centre of Australia. There’s one giant caveat, though: a final word left to Geoscience Australia, which has a particularly blunt way of deflating you after such a big, centre-punching adventure.

According to the government body’s website: “Officially, there is no centre of Australia.” The reasoning?

“This is because there are many complex but equally valid methods that can determine possible centres of a large, irregularly-shaped area – especially one that is curved by the earth’s surface.”

The curvature of the Earth is a curveball (sorry…) we hadn’t accounted for in our search-for-the-centre expedition. That and the fact that after some 5000km we’re officially no closer to discovering the true centre of Australia – if such a thing exists.

Over to you, 4×4 adventurers.

2018 MERCEDES-BENZ X250d POWER SPECS Price: $68,990 ($73,500 as tested) Engine: 2.3L 4-cylinder twin turbo-diesel Max power: 140kW at 3750rpm Max torque: 450Nm at 1500-2500rpm Gearbox: 7-speed auto 4×4 system: Part-time dual-range Kerb weight: 2161kg GVM: 3500kg Payload: 931kg GCM: 5900kg Fuel tank capacity: 80L Fuel consumption (claimed): 7.9L/100km

The Five Centre Points of Australia

Centre of gravity method Determined using 50,000 equally-weighted points around the mainland Australian border, then calculating the point at which that hypothetical cutout would balance perfectly.

Lambert Centre Otherwise known as the gravitational centre of Australia. It uses similar methodology to the centre of gravity method, but based on the high-tide mark of 24,500 points around the mainland.

Farthest point from the coastline The centre of the largest circle that can be drawn in Australia.Median point The intersection of the mid-point of the longitude and latitude extremes of the country.Johnston Geodetic Station Defined in 1965 and set up in 1966, the trigonometric survey location was set up by the Division of National Mapping as the central reference point. Modern technology, including GPS mapping, has seen modern surveys shift to the more accurate Geocentric Datum of Australia, a moving target that accounts for small movements in tectonic plates.

Centre punch Five thousand kilometres gives you plenty of time to think, especially when every second headline has something to do with Donald Trump, global warming or rising sea levels – or a combination of the three. This got us thinking about the methods used to calculate the centre of the country.

Even a small rise in sea levels could have a large impact on what is considered the centre of Australia. Larger tides in the north, for example, combined with shallow tidal flats, like those seen at Broome, could easily change the defined point of where the coastline starts by many metres, in turn requiring a recalculation of exactly where the centre is. All of which is for another day.