The whole of Australia, especially in areas with sandstone ranges, has hidden art galleries left behind by the first people who once lived here.

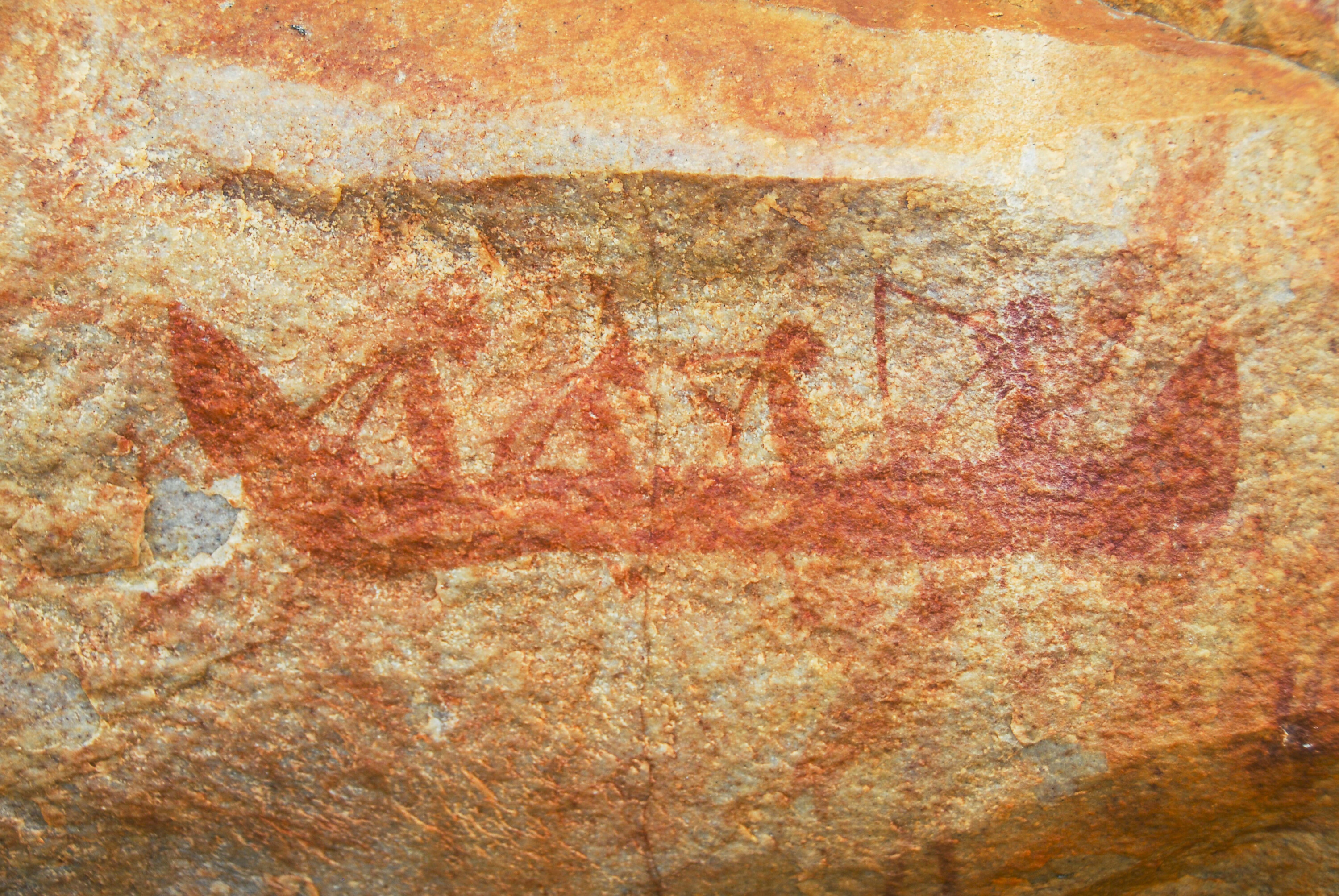

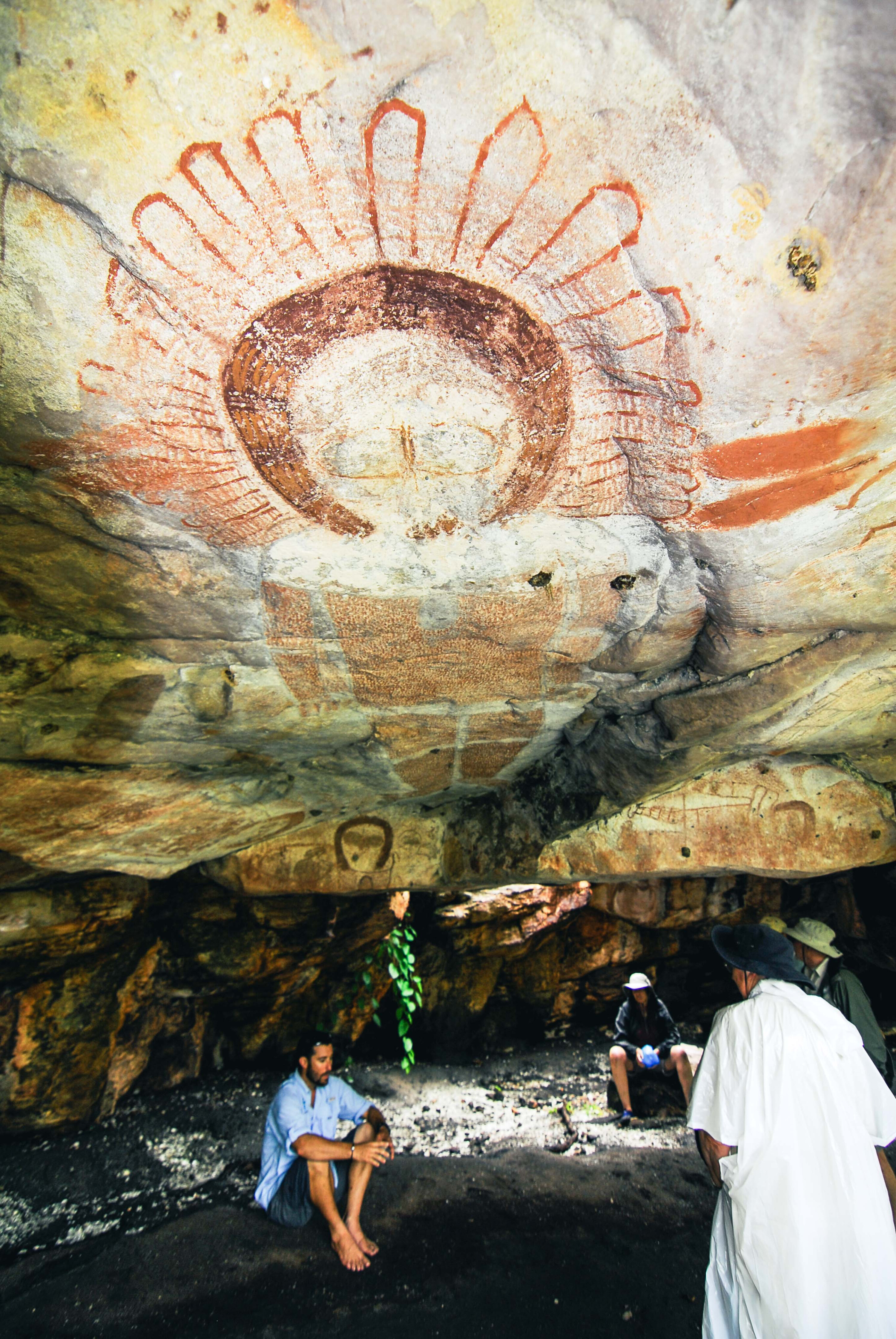

They created incredible undercover art galleries of their world including games, animals and dreamtime gods, and left behind the handprints of bored children in cave shelters when the rains tumbled down and the storm gods roamed the skies with displays of lighting and thunder that struck fear in the hearts of humans.

It’s all recorded in the art friezes, including one that I came across in western Arnhem Land depicting a lightning strike that killed a woman. But many are of hunters spearing animals, warriors engaged in battle with crocodiles, snakes and fish.

I have been fascinated by rock art since I first viewed one near Mount Isa in 1961.

The discovery led to others nearby and elsewhere in the ancient spinifex-clad ranges of the Cloncurry-Mount Isa mineral field, a region of sandstone ranges dating back to the Precambrian period that stretches into the western Gulf country and continues into the NT.

I lived in Kakadu for a decade, a place of legendary dreamtime beings that are well documented in hundreds of rock art galleries where the monsoon woodlands fringe the Arnhem Land Escarpment and its many outliers. None were open to the public in the early days, there was no policing with people exploring the region at will.

We respected the art of the ancients and none of it was damaged when Kakadu National Park was declared in 1979, which also signalled the go-ahead for the Ranger Uranium Mine where I was employed first as the Information and Housing Officer, and later in the emergency services section.

My spare time was spent fishing, hunting and exploring the hidden rock art sites where I took thousands of photographs, 35mm slides, now superseded by the digital age of photography.

I moved to the Daintree Rainforest in 1989 and operated my own tour operation out of Port Douglas before selling up and heading into semi-retirement, but when the chance came to conduct bird-watching operations for the Arnhem Land Barramundi Nature Lodge, south of Maningrida, I spent many dry seasons there taking birders into the monsoon woodlands and on the vast tidal rivers enjoying nature like nowhere else.

Conditions were such that a native guide would always accompany us to ensure we did not intrude into sacred places and other areas of significance. They were good years and under the guidance of my Indigenous brother, Stuart Aiken, I saw country that was out of bounds to others.

Stone country

The Arnhem Land Escapement is a massive wall that is up to 100m high in sections and runs for hundreds of kilometres to the north from the Roper River, and west to Kakadu, before swinging south back to the Roper.

The sandstone massif has thousands of rock art sites, many that have never been seen by living humans because the natives moved away into missions from the 1900s onwards.

Few tracks turn onto the plateau and there is only one semi-permanent settlement on it. Like elsewhere in Arnhem Land, homelands, or outstations, are abandoned at the start of the wet season, and dogs and animals are left behind when people head to the permanent villages to outsit the tempest.

I had a scientist on one trip who was so impressed that he organised his own expedition to study the paintings.

Our early season tours were the best, when tracks were still damp and no one lived at the outstations where dozens of howling kelpie/dingo cross dogs would welcome us as we drove en route to the distant red-brown bastions of the stone country looking for rare birds. It beats me how the dogs survive months of abandonment.

Birdwatchers are interested in all things nature, thus the paintings that were under the overhangs and shelters of the sandstone outliers below the 80m high escarpment were often of more interest than the birds themselves. I had a scientist on one trip who was so impressed that he organised his own expedition to study the paintings. Typically, he claimed that he had discovered them in an article in the Bulletin magazine.

There were also burial caves where the bones of the deceased were stored in paperbark wraps and in hollow logs, and elsewhere the bones littered the cave floors.

Others were stacked up high in rock hollows. Oddly there were no restrictions on some of these sites, though they were highly respected by our guides and us.

I have seen similar sites on the Victoria River and in the Kimberley, some marked at the entrance by paintings of death adders in striking positions; those were out of bounds to all and required a special dance song for entrance. In Arnhem Land we were told to talk loudly when nearing some sites so as not to startle the spirits by our sudden appearance.

The Stone Country rock art is amazing and depicts animals, fish and reptiles that are of significance to the local clan or as a food source. Various ochre colours are used; the ochre is crushed and ground from rocks and mixed with water, fish and animal oils.

Fish oil is preferred – a dead fish is laid in a small depression on the rocks, covered so that the dogs won’t eat it, and left to decay, then the oils are gathered and mixed with the ochre and crushed into a paste and watered into paint.

It’s the fish oil that permeates into the porous sandstones and drags the ochre colours with it enabling the paintings to last for thousands of years.

The are few paintings in basalt country because it is continuously breaking down and peeling, while limestone shelters have few smooth surfaces and it is too hard for fish oil to penetrate. This is why sandstone hills have the best and most durable paintings.

Where to find rock art

If you head to the Cape York Peninsula take the inland route and visit Carnarvon NP, which has amazing rock art sites that are open to the public. There are others en route in the western outliers of the Great Dividing Range, with some of the best sited in the Laura Basin.

Several Laura Quinkan rock art galleries are open to self-guided tours, while others require the services of a local Indigenous guide. The galleries are amazing in their variety of subjects, size and locations. Elsewhere on the Cape you may find isolated sites in the sandstone ranges, but few have been registered.

The Cloncurry-Mount Isa region has many sites that are reached on rough bush tracks, while to the ancient sandstone ranges run northwest to Arnhem Land with Constance Range on Lawn Hill Station having wonderful art sites and burial caves, including the Lawn Hill NP, which includes Riversleigh Station.

The ranges cross the border where years ago I explored rock art sites on Calvert Hills and Robinson River stations.

There is ‘lost’ art in the ‘Lost Cities’ south of Borroloola, and those in the Limmen Bight NP. In fact, most cave shelters here and to the north have art of some description, proof that the region had an abundance of food and water that once supported many people.

Arnhem Land is a pure wilderness and almost every rock overhang and every cave have paintings, including the southern outliers along the Roper River Highway and the roads leading into Arnhem Land proper. I have stopped near small rocky outcrops and found shelters that people once lived in, the walls blackened by smoke from campfires, others adorned with paintings and sketches.

The best is to the north of the stone country about the Liverpool River and Mount Borradaile, the eastern edge of Kakadu and farther south to Katherine.

Kakadu is arguably the best place to see cave art as many galleries are open to the public including the magnificent Ubirr and Nourlangie sites, while others require a guide.

En route to the Kimberley, the Victoria River region has a huge sandstone escarpment where the history of the people is well displayed in numerous galleries that spill all the way to Derby, but the best art is on the Kimberley Coast and can only be reached with a sea-going vessel.

However, for road travellers, Kununarra, the Gibb River Road, Halls Creek, Fitzroy Crossing and the Bungle Bungles have amazing rock art sites.

The Kimberly art is different from others and includes both Wandjina and Bradshaw styles, the latter spirit stick figurines somewhat similar to the Mimi stick spirit beings of Arnhem Land.

Some sources claim that the rock art of the Kimberley and Kakadu is over 65,000 years old, but this is not backed by academics, so don’t get carried away by the nonsense talk of some guides and other information sources when viewing art sites.

The oldest recognised art is of a Kimberley kangaroo that has been carbon dated to 17,100 years, but scientists remain at odds about reliable dating of the art.

I guess us laymen and lovers of all things nature will never know. Personally, I ignore the scientific data and just enjoy the moment and the artistic skills of an ancient people who lived in rock shelters and caves during the wet seasons, and who were bored to tears with little to do, so they painted to pass the time.

And that, my friends, is the gospel as told to me by several Indigenous mates.

Some note title here

A reliable 4×4 is needed to reach most rock art sites, although some involve hiking long distances. Sites are generally located near permanent and semi-permanent waterholes. Some sites have extensive middens comprised of bones and shellfish, and are an indicator that people lived well.

Quadbikes and trailbikes are a good way to get about the rugged sandstone ranges that art sites are located in, with most under the lee of escarpment walls and in wild gorges. In many areas permission and permits must be sought from traditional owners and landholders, though rarely in national parks.

We recommend

-

Explore WA

Exploring the remote Golden Outback in mid-west WA

This remote part of mid-west Western Australia is known as the Golden Outback, and not just because of its mining history

-

Explore

ExploreFive of the best national parks in outback Queensland

Queensland is blessed with many spectacular national parks, but here are five of the most remote, desolate, historic and breathtakingly beautiful examples

-

Opinion

OpinionTop tips for outback trips

Expert tips on outback travel, from an experienced adventurer