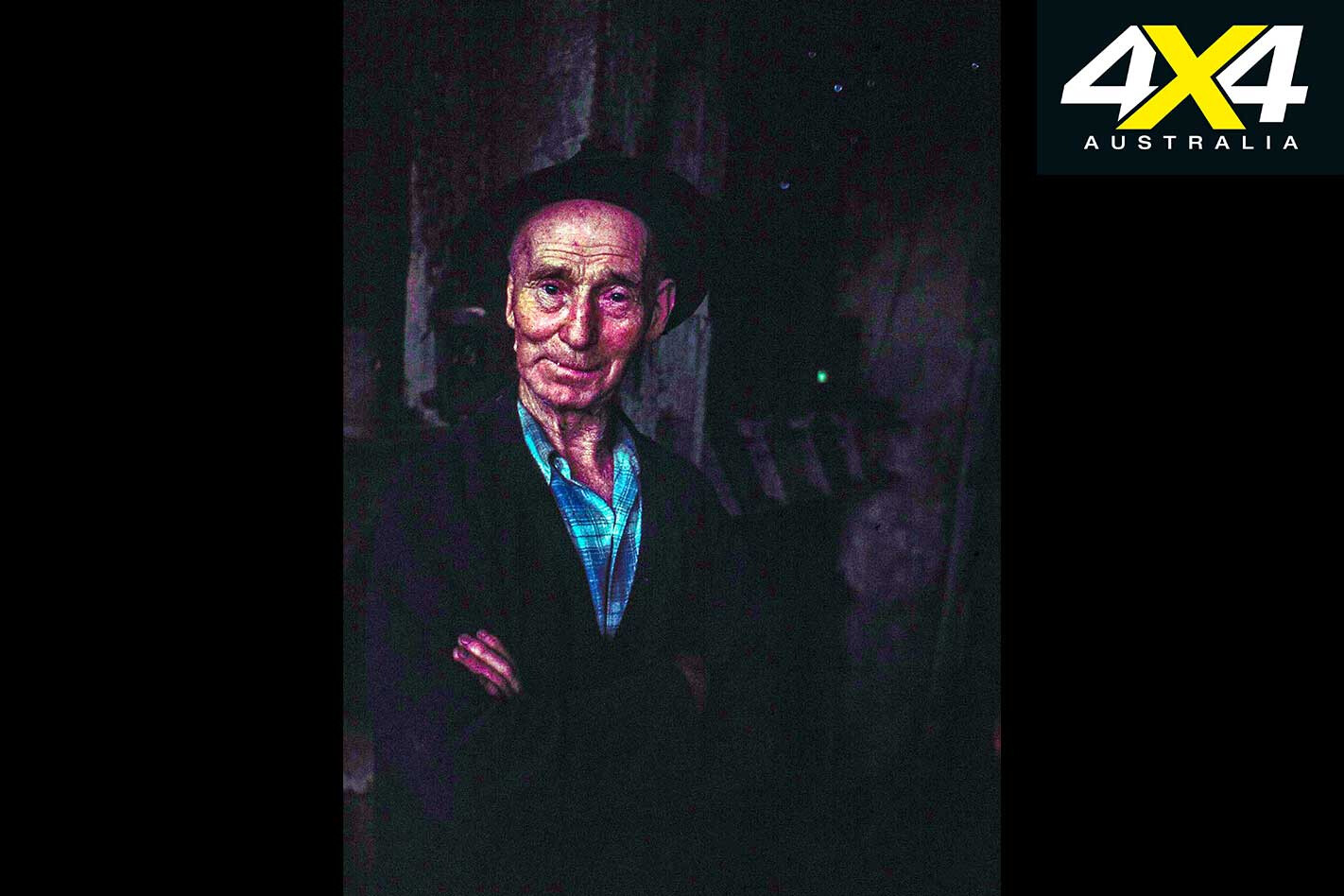

“SIT down son and I’ll tell you a story,” the old fella requested from the gloom of the dilapidated verandah of the worn-down hut overlooking the trickling mountain stream in the Victorian High Country.

“You know, there’s been more gold washed down the river since the mining stopped here than what was ever recovered.”

Over the next hour I sat with this old timer, Cecil Cooper, and I learnt a lot about gold and gold mining as it was done back in the ‘old days’. Old Cec was the caretaker of the Maude and Yellow Girl mine back when I first met him and his face showed the wear and tear of a lifetime spent in the mountains looking for and mining gold.

Born at Glen Wills in 1898, he passed away in the 1990s still living a rough, tough life in a tin shanty on the edge of Swifts Creek, just downstream from the ruins of the King Cassilis mine.

Now I was back again at what remained of the Maude and Yellow Girl mines and their processing plants, two of the most important mines in the Victorian Alps and now located in the Mt Wills Historic Area north of Omeo. The track to the site can be easily missed, but it is just a couple of kilometres north of the Big River Bridge camping area on the Omeo Highway.

However, instead of taking the torturous bitumen road north from Omeo, head along the Omeo Valley Road to Hinnomunjie, where you’ll cross the Mitta Mitta River with a spacious and top camping spot just downstream. For engineering buffs the Hinnomunjie Bridge, built in 1910, is one of a very few timber truss bridges still in existence and the only one constructed using hand-hewn timbers.

Then, just north of the Mitta, take the Knocker Track – the historic stage and wagon route from Omeo to Sunnyside/Glen Valley, where all the heavy equipment for the many mines in the area was hauled by hardworking bullock teams. Today, the route is often used by logging trucks, so take care.

Once on the Omeo Highway, turn south and stop at the notable Glen Wills Cemetery with its lines of white crosses, many belonging to young kids who died in what was then a pretty remote place in the High Country. You’ll pass through the scattered hamlet of Glen Valley and then arrive at the turn-off to the Maude and Yellow Girl.

A bumpy track across the paddock to the creek will bring you to the parking area for the short walk to the Yellow Girl, while a longer walk down the creek will bring you to the battery and large processing shed of the Maude mine.

Severely damaged in the 2003 fires, the old shed over the historic Ruston Engine at the Yellow Girl has been replaced by a modern galvanised structure which takes away a little from the historic context, but the work being done on the old engine is nothing short of marvellous. Now back in running condition due to the work of a small group of enthusiasts led by mining engineer, Ted Giliam, the 200hp engine is the only one in running condition in Australia.

Just downstream, the original large shed still stands over the Maude battery site. While much of the equipment has been stripped and stolen (which is why the vehicle access track has been closed) and the 20-head stamper is a tumbled mess after the fires, it is still an impressive mining site to visit.

From here we headed to Omeo, once the centre of a booming alluvial goldfield which today has a rich heritage of gold mining and mountain cattlemen to admire and remember. It’s a top little mountain town with a very pleasant campground spread along the picturesque Livingstone Creek, while the local museum and outdoor display in the heart of the town is not to be missed. We threw down our swags behind the Top Pub where you can enjoy free camping, along with a cold beer and a great meal in the hotel.

Just south of the town along Livingstone Creek is the Oriental Claims Historic Area, an alluvial field that was worked for more than 50 years, starting in 1851.

Walking trails wander along the creek below high bluffs, the result of the hydraulic sluicing that was used in the mad scramble to flush gold out of the soil. Nearly 60,000oz of gold was recovered, but the creek ran (or oozed) with so much sludge and the pollution was so bad that the Sludge Abatement Board was formed, and in 1904 it banned all sluicing along the creek.

Our travels continued, taking the back road from Omeo to Swifts Creek which takes you through the hamlet of Cassilis and to the turnoff to Powers Gully and the King Cassilis Mine. The mines here reached their peak in the 1890s, but by World War I most had closed and the town rapidly declined.

Spasmodic mining operations in the 1980s found little gold but, sadly, destroyed much of the integrity of the old mine site. There is still a host of old mining equipment scattered around the site, while the main audit to the mine can be found farther up the hill. In Power’s Gully, a very large expanse of mine tailings can be seen.

From here, a great little 4WD track heads up the surrounding hills; in fact, there are quite a few tracks through these steep hills, but this time we took the Charlotte Spur Track. This old wagon byway passes through part of the historic area before climbing a ridge and sneaking past a nearby farmhouse. From here it deteriorates, climbing steeply up through box gum woodland and along the steep edge of a hill, where sections of packed-rock retaining walls can be seen.

It’s a steep, rocky scramble in places where anything bwedgeut a ‘real’ 4WD would have extreme difficulty in getting through. Once on top of the ridge we found our way onto the Bayliss Spur Road and then onto the better Mt Delusion Road, finally arriving on the major dirt throughway of the Upper Livingstone Road.

Just before that latter junction, the road crosses a section of the old, now-disused, Jernkee Water Race, which took water from the headwaters of the Wentworth River to the Cassilis mines, some 77km away. The longest hand-dug water race in the southern hemisphere, it was a complete disaster and soon fell into disuse.

Turning west we took Birregun Road and paid a visit to the Dog’s Grave, the best monument you’ll find to ‘man’s best friend’, before cresting Mt Birregun, with its helicopter pad and tall communication tower, for an extensive view over East Gippsland.

An hour or so later we cruised into the mountain township of Dargo, a hugely popular 4WD destination whether you are into touring, fishing, hunting, bushwalking, panning for gold or doing sweet bugger-all in an idyllic setting.

Dargo was never a gold-mining town as such, but rather a wayside stop and supply point for pioneer miners and cattlemen finding their way to the goldfields of Grant and Crooked River, or across the mountains through the Wonnangatta Valley to the Howqua Hills and Mansfield.

It still does much the same today; although, most of the people passing through are recreational travellers looking for a High Country adventure and an escape from the city life. With the attraction of the pub and a meal, along with the fact it was raining, it was quickly decided to bunk at the hotel and enjoy its warm hospitality.

Our route took us north to the once rich and busy settlement of Grant, now completely deserted and near lost in the rich regrowth of the forest. Still, you can visit the old cemetery or, with a bit more diligence, find your way to some of the mines that made this town such a busy one back in the 1890s.

We descended Bulltown Spur, which is always an interesting pitch down to the Crooked River – low-range first-gear is always good here – and its many water crossings, before arriving at the cleared area that was once the site of the township of Talbotville.

Along the way you’ll pass a track that climbs steeply to a rough carpark, where a walking track meant for mountain goats leads upwards to the ruins of the Good Hope Goldmine and its steam engine and stamper. The walk is strenuous, but worth it.

At Talbotville the large, cleared area along the edge of the Crooked River plays host to a lot of campers, but I’ve yet to see it full; most times there are only a couple of camps spread across the grass.

For the early miners and the pioneer cattlemen the trek from here across the mountains to the Howqua River and its goldfields was a long and tough one. Most headed to Eaglevale on the Wonnangatta River and then climbed the range over the top of Mt Cynthia to follow the Wombat Spur, before dropping down into the ‘Hidden valley of the Alps’ at the remote Wonnangatta Station.

As it was dry, we did much the same, taking the very steep Herne Spur track into the valley. We wouldn’t recommend this route if it is wet, as the clay surface and the steepness of the route can be a dangerous combination.

Our stay in Wonnangatta was short and uneventful, as we took the long, sinuous Zeka Spur Track up to the Howitt High Plains and on to historic Howitt Hut. This hut was built in the early 1900s by the Bryce Family who owned Wonnangatta at the time and ran their cattle across these high plains during summer. We didn’t stay in the hut, preferring the grass beneath the nearby snow gums.

The next day we headed north on the gravel of Howitt Plains Road, which soon became a track and then a rough, rocky thoroughfare as it descended into the Macalister River valley and its headwaters. This is a delightful stream, but the amount of timber down, which inhibits any form of access to the water, is totally unbelievable. Annual track clearing by Parks and 4WD Victoria keeps the route open most of the time, but, if you’re planning to go through here, a chainsaw may be a good investment.

The climb up the other side is no less rough, and there’ll be relief when you reach the snow gum-surrounded grassy meadow at the saddle of King Billy. From here our route swung along the ridge – the track much improved after a lot of work by Parks Victoria – passing through a virtual tunnel of snow gums before coming to the King Billy Tree, recognised as one of the 50 most significant trees in Victoria.

Estimated to be between 400 and 600 years old, this tangled, stunted giant could tell a story or two. From there the track passes Picture Point, made famous in The Man from Snowy River films, before descending to Lovicks Hut and then Bluff Hut, where we met up with two iconic mountain cattlemen, Charlie Lovick and Graeme Stoney. We had a great night around the fire that night.

The next day we dropped down off the range to the Howqua River, meeting up with another mountain cattlemen family, Bruce McCormack and his daughter, Cassie, who were out taking a group of riders through some of the most spectacular parts of the High Country. It’s a fabulous way to experience the mountains and get a taste of what the pioneers saw and lived every day of their lives.

Downstream, the Howqua runs through gold-bearing country, and, down near Tunnel Bend and the small river flats that are so popular with campers, it enters the Howqua Hills Historic Area. Little remains of those heady days of gold; although, the brick chimney and smelting furnace dating from 1884 can still be seen along the walking track between Sheepyard Flat and Frys Flat.

We headed to Frys Hut and the flat of the same name; the hut dates back to the times of Fred Fry, a master bushman and hut builder who lived here until his death in 1971.

It was a fitting end to our trip following the footsteps of gold seekers, and, like most people, we’ll return to relive it all again and have more adventures in the Victorian High Country.

Travel Planner

Omeo: www.omeoregion.com.au

For info on the parks and the historic areas, visit: http://parkweb.vic.gov.au/

For info on the Ruston engine, phone the Omeo office of Parks Victoria: (03) 5159 0600

Dargo township: www.visitgippsland.com.au/destinations/central-gippsland