THE WHEEL marks went up and over the dry, grass-covered sand hill, but as we’d been asked by the property manager not to drive on the dunes I got out of the Cruiser and wandered to the top of the low rise.

To the east and south, flat and grassy plains near devoid of anything taller than half a metre stretched to the horizon; while to the north a salty flat bordered an inlet of light blue-green water where short and narrow strips of mangroves gathered to find a foothold on this remote coast.

As I topped the hill, a series of dunes parallel to the one I was standing on marched their way towards the ocean just a few hundred metres away which was wild and wind-capped. Almost at my feet, near smothered in the grass, was what we had come to find: an old cemetery from a long-abandoned pearling port … if you can call three or four markers a cemetery.

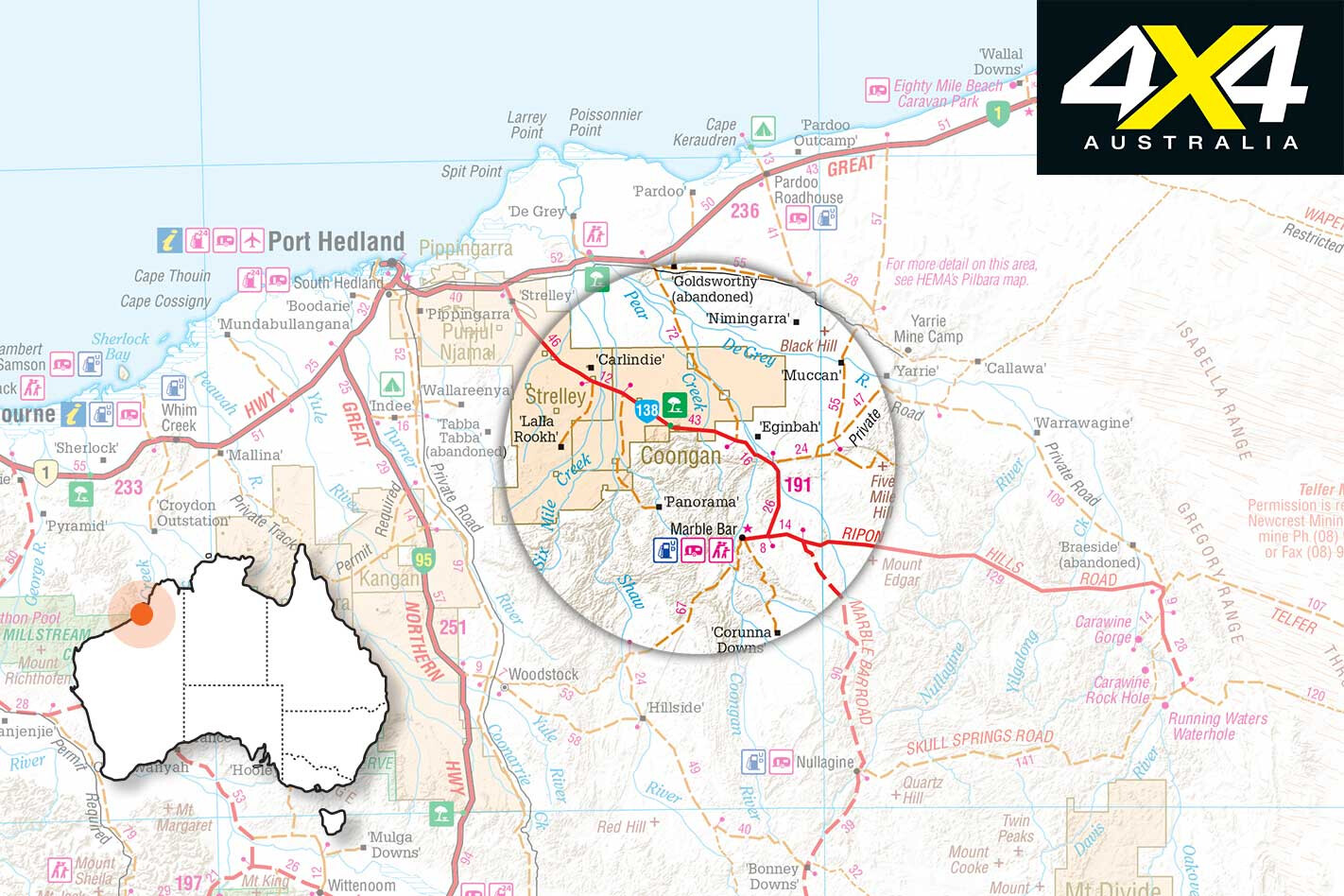

We were at Condon, the once important shipping outlet on the far north-west coast of WA, which few people have heard about and even less have visited. Gazetted as Shellborough but rarely known as such, Condon was the first port established along this long-deserted section of coast.

Situated north of the De Grey River mouth, the area was surveyed in 1872. The surrounding De Grey pastoral station, then running sheep, had begun 10 years earlier, a year after Frank T Gregory had explored the area and reported the expanse of rich grasslands.

The tiny hamlet initially provided a shipping point for wool sent direct to London, but it grew in importance with the discovery of gold at Marble Bar and Nullagine in the 1880s. Pearling luggers also used the shallow harbour, with up to 80 boats anchoring here – it’s hard to believe that these days, when the only boat within cooee would be a fisherman’s tinnie.

By the 1890s the town, with a population of about 200, had a couple of hotels, a stone jetty, customs shed, a number of stores, blacksmith shop, telegraph station, and a woolshed and stock yards. Because of the huge tides, the larger ships would sit on the mud as far out as a kilometre from the shore for loading and unloading, while only the smaller ships and luggers would tie up to the stone wharf.

Today the old rock wharf has collapsed (it once stood at least two metres high) and is just a line of flat stones jutting out from the sandy southern shore. The sole timber pylon or strainer post that stood 25 years ago when I first visited the site has disappeared, while the only reminder of the customs shed and other buildings is an occasional stump among the tall grass.

A cluster of tamarisk trees just up from the jetty is the only obvious marker in the whole area and makes probably the best camp for those who want to stay here. However, while we were wandering around, we spotted another camp on the northern shore of the inlet in a fairly exposed spot with good boat access to the inlet – keen fisherman, I’m guessing.

Our travels to Condon originally began back in 1991 when we were following the footsteps of the 1879 Alexander Forrest expedition. His expedition, like ours, started at Condon, but we didn’t have time to explore the surrounding area then, so I knew we’d be back. When we returned just a few years ago, unseasonal rain meant the De Grey Station owners stopped access as the flat country was easily flooded and tracks were damaged by vehicles ploughing through the mud.

This time we were luckier and, while I had no luck on the phone ringing the homestead, we thought we’d try our luck and just rock up to the property headquarters. The De Grey Station, founded in 1862, is more than 12,000km² in size – or around three million acres.

The well-run and rich property comprises a manager’s quarters, staff accommodation, work sheds, solar panel arrays, trucking yards and machinery of all sorts including graders, front-end loaders, road trains and Land Cruisers. Still, we hardly saw a cow on our way there.

After meeting with and receiving directions from one of the managers, we headed off on some pretty easy tracks across the vast plains. The last 15km of tracks to the coast and Condon follow the route of the original telegraph line, with the occasional old pole complete with insulator still standing and running in a direct line towards our destination.

You pass the remains of the telegraph office, which helped link a distant Derby with Perth, a few kilometres short of the actual port of Condon. A forlorn solitary telegraph pole today overlooks the site, along with a tall date palm and a large flowering, scraggly oleander tree.

Just over the dune from the old telegraph station were the graves we had been told about but never saw on our previous visit. There are 11 souls buried here, but only a headstone and a few rusty steel enclosures now mark the hallowed ground.

With that success behind us we went in search of other treasures, and those who wander the wider area will find the occasional rubbish dump strewn with broken bottles and pottery shards. For most people, though, the main attractions include the isolation, beach combing (the shell collecting is pretty darn good), mud crabbing and fishing.

Remember there are no facilities and there’s no firewood at Condon, so you have to bring your own wood. You can launch a small tinnie off the beach in the inlet a few hundred metres upstream from where the old jetty can be seen, but be super cautious launching from anywhere else due to the soft sand and tides.

Plus, avoid driving on the dunes around Condon, as it only leads to erosion. A few years back the property closed entry to the entire place because of the damage and rubbish left behind. It took a couple of years of lobbying by the local shire before they decided they’d re-open access to courteous locals and clean-thinking travellers.

From near here you can swing inland to cross the upper reaches of the inlet and head north to a couple of smaller inlets, the biggest of which is Titchella Creek.

Access to here is also possible from Pardoo Homestead, which now offers travellers good camping, accommodation and even a cold beer at well-established facilities.

We’d camped for the night near the highway, where it crosses the De Grey River. It’s a popular camp for grey nomads, but fencing and rock barriers have been installed to stop people and stock accessing the riverbank because of the threat of the invading noogoora burr plant.

That noxious weed has already closed off long lengths of river frontage along the Fitzroy, a few hundred kilometres to the north, with workers trying to stop the same happening here. It’s a big ask, with the property owner, the Department of Agriculture and many volunteers actively trying to stop the invasion; so give them a hand and don’t enter fenced-off areas. Also, don’t transport any seeds you get stuck with – you’ll know the spiky buggers if and when you find them.

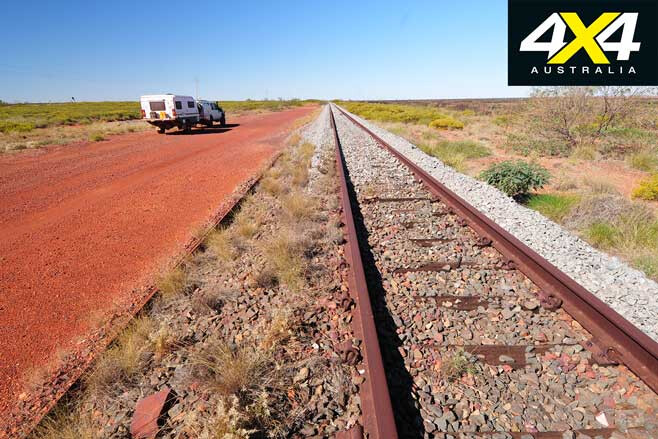

After our Condon experience we headed inland to Shay Gap, by following the now disused railway line that heads from its crossing of the De Grey River near the overnight camping area. Shay Gap, a deserted, basically non-existent town that closed down in the early 1990s, was named after the nearby break in the ranges of the same name, which in turn was named after Robert Shea.

He was the part-owner of the pearling lugger Seaspray and would have almost definitely used Condon as his port for his enterprises back in the 1870s. He headed inland looking to find some of his indentured labourers who had absconded, and he was probably killed by them or their compatriots. This isn’t a surprise, as Robert Shea and his like weren’t particularly nice people, abducting many people and forcing them to dive for pearl shells.

A good dirt road follows the railway line, with our journey only interrupted by flowering cassia bushes and a derailed train that had dumped iron ore and carriages beside the track. As we closed in on the range that acts as a barrier to the shifting sands of the Great Sandy Desert, we could see piles of overburden and the remains of the mining operations that had been carried out between 1972 and 1993.

We left the railway and dodged north around the numerous mining sites to meet up with a bitumen road which took us south towards the dismantled town; the only building still standing is the one at the airport, which still gets used by exploration and mining survey crews by all accounts. That evening we camped in Shay Gap, off the dirt road and surrounded by rich red bluffs, buttes and pinnacles of rock.

We were tucked in beside Coonieena Creek, which was dotted with drying pools of water.

The next day we headed south, crossing the De Grey River near Muccanoo Pool – close to where Robert Shea was reputedly killed – and then the Talga River before we hit the bitumen. Here we turned west for a short distance before finding our way into Doolena Gap, where the Coongan River cuts through the range before joining with the De Grey. It’s a top spot to camp.

For the next couple of days we explored in and around Marble Bar, a town famous for suffering the longest consecutive time – 161 days – of the temperature not dropping below 37.8°C (or 100°F). That was back in 1924, and the record still stands.

The town got its name from a rock bar across the nearby Coongan River; and while the bar isn’t marble it still cuts a pretty sight, especially when the rock is splashed with water. Marble Bar is attractive and much more hospitable than most first-time visitors would assume, with the small town’s setting among the rugged, rocky hills making it much more than a desert hamlet.

Gold was discovered here back in the 1890s, with some big nuggets found including the ‘Bobby Dazzler’ at 413oz (or 11.7kg), the 333oz ‘Little Hero’ and the 332oz ‘General Gordon’. Metal detectors are de rigueur for travellers to this part of the Pilbara, with fields including Sharks Gully, North Pole, Talga Talga and Twenty Ounce Gully still producing nuggets today.

If you’re a history buff then Ernest Giles at Glen Herring Gorge, south of the town, is worth exploring and isn’t a bad spot to camp. About 50km south of the town, the remains and airstrips of the WWII Corunna Airfield – the secret base where American and Australian bombers flew from to bomb Japanese forces in Indonesia – can be found.

On this trip we popped into the Meentheena Veterans Retreat, which not only caters for veterans but for everyone. Meentheena, about 80km east of Marble Bar, was once a pastoral property straddling the upper reaches of the Talga and Nullagine Rivers. It’s now a conservation park, and the Veterans Retreat of WA now operates camping, accommodation and controls access, all in a low-key manner.

Bush campsites along shaded stretches of water of the Nullagine River have been established, while rough bush tracks lead to points of interest. For those who can’t tear themselves away from the modern world, the retreat’s HQ has powered camping and caravan sites, camp kitchen, hot showers and internet access. You could easily spend a few days here.

With our time up we took one last look at the old town and vowed we’d come back and take a journey from the sea to the mountains once more. You should do the same.

Condon to Marble Bar Travel Planner

Pardoo Homestead: www.pardoostation.com.au Marble Bar: www.australiasnorthwest.com/destination/marble-bar Meentheena Retreat: www.vrwa-meentheena.org