When I arrived, the air was so still I could hear the distant call of crows from kilometres away, and there was no one around as I wandered about the deserted railway station in the late afternoon light, feeling like the last man on earth.

As day turned to dusk, and then twilight, I saw a light in the distance. A train was coming, the intensity of its headlight growing and the high-pitched hum of the loco on the tracks becoming a roar before the heavily loaded freight thundered through the station at close to 100km/h, leaving a rush of air in its wake before silence eventually resumed.

With a new moon, the starlight was brilliant, so I set up my camera for a time-lapse, retired to my swag and fell asleep under the spectacular star show above me. At midnight, I was stirred by a wind that had come up. Rawlinna is in a basin on the edge of the Nullarbor Plain and as the wind blew over the flat land it quickly increased to a gale, becoming so strong I had to take my camera from the tripod … and it howled all night. I was later told Rawlinna means wind.

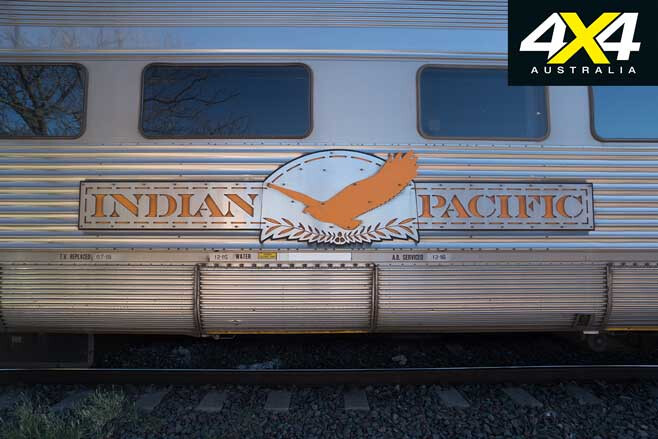

By dawn the air was still again, and I explored the station. The old post office and storefront looked like they could still open for business; they were built to last out of red brick and corrugated iron. The post office isn’t manned but apparently it’s still possible to post a letter here, as there’s a box and ‘6434’ postcode.

Across the tracks the tall water tower still stands but has certainly seen better days. These magnificent towers are striking features at many of the old sidings across the Nullarbor. During construction of the railway this place was one of the main depots, and it was named Rawlinna in 1915. Rawlinna also played a part in the construction of the Eyre Highway in 1941-42 for supplies arriving by train.

In 1901, when Australia was federated, Western Australia relied on the sea for transport. It was agreed a railway would link Western Australia to the other states and this was legislated in 1907. It was to join Kalgoorlie and Port Augusta by standard gauge and construction began at each site in September 1912, with work progressing quickly before it was joined at Ooldea on October 17, 1917. The Trans Australia Railway recently celebrated its 100-year anniversary at Ooldea.

When finished the distance was 1692km and the water to power the locomotives was provided by bores, however much of the water still had to be carried by the trains.

In the days of high track maintenance Rawlinna had a regular population with a school, the remains of which are on the edge of town. There used to be gangs based in Rawlinna, but then the track’s sleepers were changed from wood to concrete and regular maintenance wasn’t required. Trains also became longer with greater range, so today the town is virtually deserted, except for a ’roo shooter and some regular railway workers.

Close by is Rawlinna Station – one of the largest sheep stations in Australia. With an area of one million hectares (2.5 million acres), it can take up to eight hours to muster a paddock and the station can hold up to 80,000 sheep. In 2018 there were 64,000 sheep sheared for a wool clip of 1500 bales. Rawlinna is also the site of the Loongana Lime Mine, which is only a few kilometres from town and clearly visible. There are power lines heading out to the mine and workers’ sheds scattered about. Rawlinna also has a huge loop track. Some of the trains that head through the station here are 3km long.

Rawlinna is on the western edge of the Nullarbor, 910km from Perth, and heading east it’s flat for 660km until you reach Ooldea. Along this stretch the track runs dead straight for 478km, making it the longest straight section of track in the world. This is the true Nullarbor, where the horizon surrounds you and there are just occasional stands of trees.

The permit-only unsealed road that runs beside the railway is for maintenance workers. You can access certain sections from the highway at Cook and Ooldea, and you can also drive out to Tarcoola from the Stuart Highway. I’ve travelled in both directions across the Nullarbor on the Indian Pacific, and looking out across the endless plain is mesmerising on this amazing train journey.

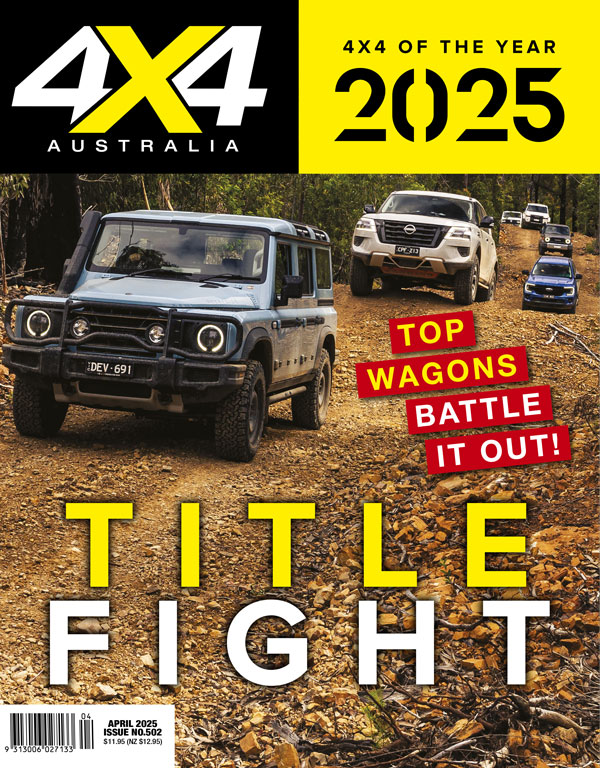

Just after sunrise at Rawlinna I glimpsed the Indian Pacific’s light as it headed towards me from the west. The train had left Perth a day prior and travelled through the night. It slowly pulled into the station, a single blue and yellow locomotive with an eagle emblazoned on its front towing a kilometre of gleaming silver carriages.

Eventually the passengers emerged; the two-hour morning tea stopover at Rawlinna is a regular schedule for eastbound passengers. Westbound passengers also stop here for an evening meal under the stars. If you are here, it’s a great opportunity to see the train pulled up in the middle of nowhere.

I had followed the same route as the train and driven the 375km unsealed Trans Access Road from Kalgoorlie out to Rawlinna. The road passes by mines and then through tall woodlands, and there are glimpses of the railway along the way. It’s a rough track in places and any potholes are filled with sharp stones, so be careful as this road can be a tyre killer. On occasions I left the road completely to bypass long sections of these stones. Close to Rawlinna the woodland turns to scrub and then flat limestone.

There are no services at Rawlinna, no shops nor accommodation, so you need to carry all necessities including fuel and water. As a result, the nights out here are magical; there’s no glow from any external lights and you can see the headlights of the trains coming from many kilometres away.

I took the Haig Road south to the Eyre Highway, which starts about 70km to the east of Rawlinna, at what used to be the Haig Siding. The 100km track to the highway is dirt with lots of gates, and this area quickly becomes impassable after rain. During the day kangaroos rest under low bushes on the side of the track.

Once you reach Cocklebiddy you feel like you’re back in the real world. There’s a shop, accommodation and a pub … with great food. You can also fill your tank and water bottles, and have a shower.

There are a few attractions around Cocklebiddy, so it’s worth staying around if you have the time. There are about 20 huge caves on the Nullarbor, which is the largest karst (limestone) area in the world. If the rainfall was higher there would be more extensive weathering and the landscape wouldn’t be so flat.

Many of the caves have lakes of clear water and are frequented by divers. The track to Cocklebiddy Cave is 12km west of Cocklebiddy and 10km north. The cave has been explored underwater for more than 6km, and while you can see the entrance, access is closed to the public.

There are also blowholes near the highway close to Cocklebiddy – these amazing holes blow air when the cave breathes as air pressure falls and rises. Air movement in caves has been measured at about 70km/h, and smaller caves breathe air with more force.

To the east is the Eyre Bird Observatory, established by Birds Australia in 1977. It’s in the old telegraph station building that was built out of limestone in 1897, which was left as a ruin in 1930 and restored in 1977. You can stay overnight or day visit for a fee, but you must contact the caretakers and book ahead. The turnoff is 17km east of Cocklebiddy, and it leads to a scarp, with the last part of the track descending a cliff and is 4×4-access only.

The bird observatory is obviously popular among twitchers, and around the station are many Major Mitchell’s cockatoos, along with a huge range of other bird species in the area. There are also possums, kangaroos and other fauna.

The observatory runs courses at different times of the year, including one on bird photography. There is also a museum with amazing collections including whale bones and old tools and gear that were used by the original settlers. You can walk down to the beach from the telegraph station, and the coast is beautiful with pure white dunes.

South of Cocklebiddy is some stunning coastline, much of it part of the Nuytsland Nature Reserve which covers more than 500km of coast. There are tall dunes, cliffs, coves and unique vegetation such as rare species of banksias. The wide variety of wildlife you’ll see includes eagles and dingoes, and offshore there are whales, seals and dolphins, while beneath the waves are reefs and crayfish. The one thing you won’t see too much of is people.

If you head down to Twilight Cove there’s a good chance you will want to stay for a few days, so head off with this in mind. The track to Twilight Cove starts behind Cocklebiddy Roadhouse and is only 26km, but it’s rough rock in places. There are also soft sand sections, so you’ll have to reduce tyre pressures. The track is also narrow and heavily vegetated, so it can scratch your vehicle. It may also be impassable after rains, so come prepared and bring recovery gear.

When you get close to the coast the track traverses a major dune system. In 2017 a huge bushfire ravaged these dunes and trees were burnt out for as far as you could see. On the last section before the beach the track gets soft and you have to traverse steep sand hills.

There are high dunes, and to get onto the beach you have to cross over them. It’s a long, open beach and there are nice sites to set up a camp among the dunes. Close to the water the sand is very soft, and the waves break on the shore forming deep gullies, so it can be a treacherous beach for driving on in anything but very low tides and swell.

At the western end of the cove are the magnificent Baxter Cliffs; these 70 to 100m spectacular cliffs have amazing bands and patterns in them. They stretch continuously for 190km, from past Israelite Bay to the west, and at Twilight Cove they head inland all the way to Eyre. The Cove was named after a ship called Twilight that was wrecked here in 1877, when the Telegraph line was being built. There are also signs of the past including the remains of old telegraph poles.

If you like the isolated beach life, this is a great spot. I’ve been stopping here for 20 years on my regular trips across to WA. There is terrific beach fishing, it’s good for a swim in the warmer months, and the photography is great. Who doesn’t love a magnificent isolated beach?