Any new tech that makes your vehicle more capable off-road and more comfortable on-road has got to be a win-win, right? Exactly, which is why you went out and bought the latest adjustable, bypass dampers that were once the preserve of the off-road racing crowd but are increasingly finding their way onto road-going 4x4s.

But now that you’ve fitted the shocks and had a fiddle with the various adjustments, the car has gone from a capable all-rounder to something that either wants to fall over or rides like a bed of nails. Not only is your vehicle now potentially less capable, but it’s cost you several grand to get here. Something’s wrong!

Yep, you bet it is, but according to the experts there are multiple causes, and, oddly, none of them really involves the end user messing around with something he or she doesn’t understand. Nope, the problems often start because these new shocks are not widely understood by everybody selling and fitting them.

Also, it’s not necessarily that your shiny, high-end new shocks have been set up incorrectly, but rather that they’ve never been set up at all. And finally, there’s our old friend the internet which is happy to sell you a set of shocks and then leave you high and dry when it comes to how to use them.

In fact, about the only factor the experts will rule out is operator error, because even though these shocks do have adjusters built into them, those same adjusters don’t make huge alterations. Michael Zacka, who runs Mike’s Shock Shop, reckons the only tuneable-on-the-trail aspect is a small part of the ride zone.

So if you’ve bought high-end bypass shocks with the aim of having a magic-carpet ride one day and leaping off sand dunes the next with the simple turn of an adjuster screw, you might just be disappointed.

According to Ben Napier of Solve Off Road, compromises can be involved way back when the product is being developed.

“Generally,” says Ben, “a shock manufacturer will get hold of the make and model vehicle they want to develop the product for. The problem with that is that the development vehicle will be a, say, Ford Ranger, but it’ll be a stock-standard, unmodified car with the OE plastic bumper.

Now, I don’t reckon there’s a single stock-standard Ford Ranger in this country. Certainly not one where the owner is prepared to spend up big on high-end shocks. We call that the Australian factor.

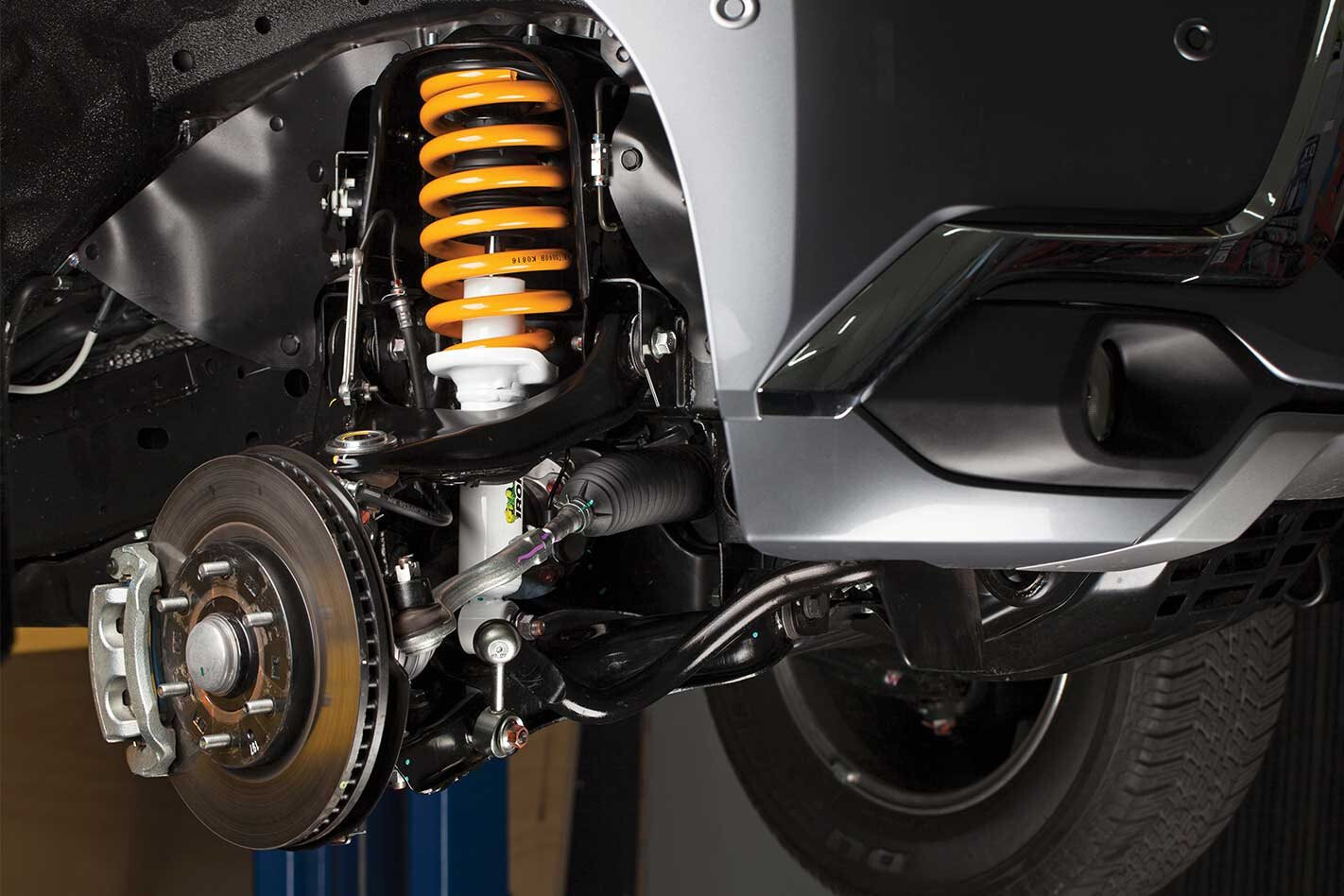

“With this high-end stuff, particularly the coil-over type, a lot of people need a stiffer spring component to carry the weight of a bullbar and winch. But when that stiffer spring becomes unloaded at speed, suddenly you have a horrible-riding vehicle. That calls for a completely tuneable shock, which these are, but we’re talking internal adjustments, not fiddling with the damping adjuster at home.”

Ben reckons that even though plenty of research and development goes into these shocks, a coil-over kit for something like a dual-cab ute or a Toyota 200 Series will very rarely leave the Solve workshop without some kind of internal adjustment to make them fit for purpose and to optimise the owner’s spend. “Only then will you get the full benefit,” he says.

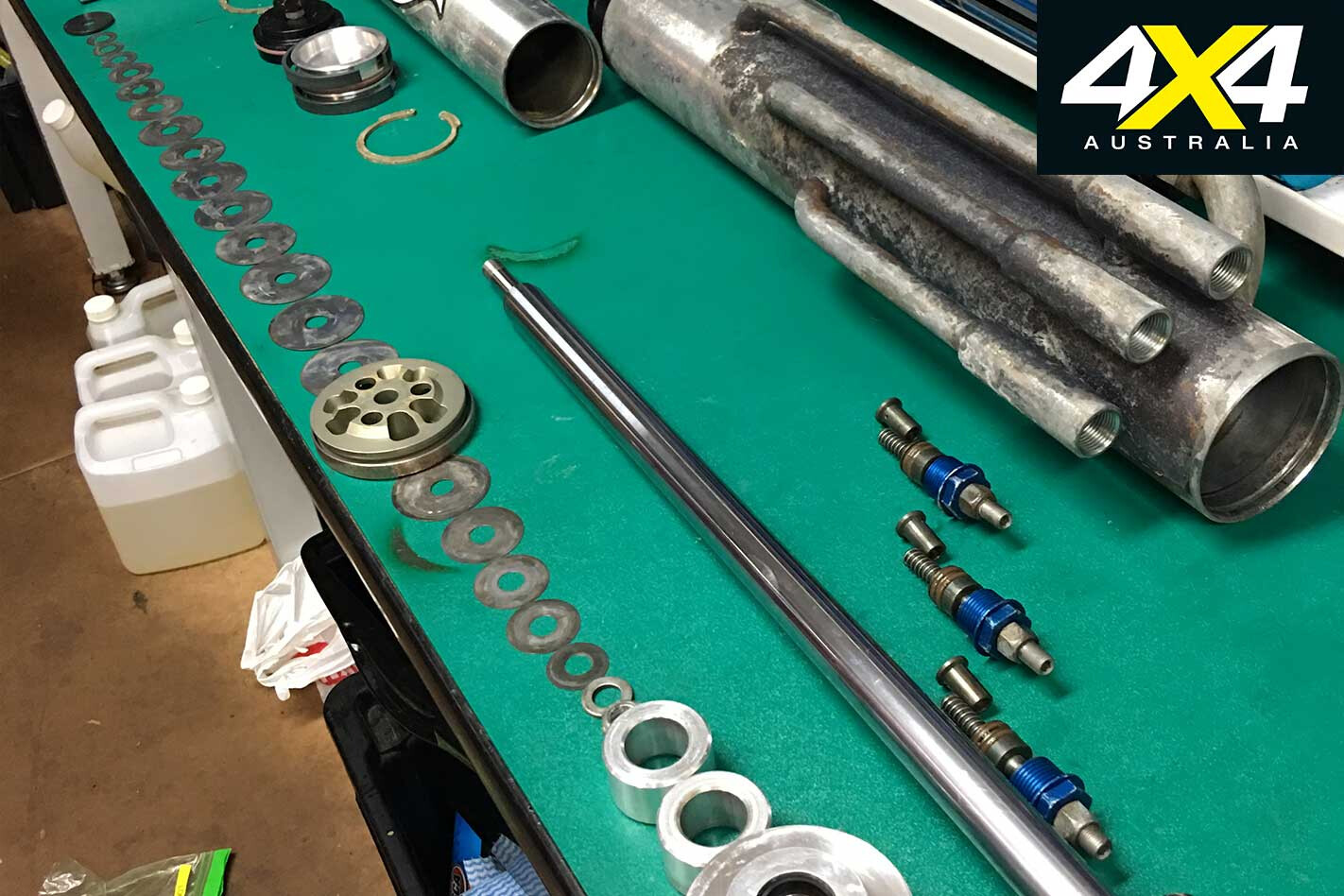

In the case of Mike’s Shock Shop, there’s a comprehensive spec sheet the owner needs to complete to get the new shocks set up properly, before a spanner has even been turned. There’s obvious stuff like whether there are long-range tanks or dual batteries fitted, but there’s also nth-degree details like whether the winch has a steel or synthetic cable.

Clearly, buying a set of shocks online, bolting them on at home and crossing your fingers isn’t the way forward here, and it kind of guarantees that you won’t get the best out of the technology.

But don’t the adjusters built into the damper allow for this sort of stuff? Not really, and Ben’s view is similar to Michael Zacka’s in that the external adjusters that are part of the shock are really only for small-increment adjustments to the ride quality. “The adjusters only really amount to extreme fine-tuning of the damping valving,” he says. “If the fundamentals aren’t right in the first place, you can fiddle with those all you want and achieve very little. The fact is, there’s no such thing as a gun off-the-shelf setup.”

One area where the end user does come in for a bit of criticism is when they’ve fitted coil-overs with height adjustment (usually via a C-spanner). Ben Napier reckons that most of these shock kits are designed for vehicles already running, say, a 2.5-inch lift. But trying for a bit more by winding the spring up could be asking for trouble.

Michael Zacka agrees and reckons a large part of the dissatisfaction at consumer level occurs when people ask too much of the product. “People with IFS front ends trying to lift them beyond about 70mm is a real problem,” he says. “It leaves the vehicle with no droop.

Essentially, if that’s what you’re trying to do with factory geometry, you’ll need a dental plan.”

Okay, so that’s fine if you’re shopping at the very highest end of things, but a lot of four-wheel-drive owners are looking for something better than the stock replacement, but have neither the budget nor the requirement for the performance of those bespoke setups. For such owners the news is good, with a range of more wallet-friendly bypass shocks entering the market in recent times.

ARB’s Old Man Emu-branded BP-51 shocks are a great example and, according to ARB, are tailored to a particular make and model, while also incorporating bump and rebound damping for adjusting ride quality.

Spring preload is also adjustable on some models. Because they’re designed for a specific fitment, ARB says they don’t need internal adjustment before fitting, but that to maximise the effect of the shocks they should be considered part of an overall suspension upgrade rather than just in isolation.

ARB is quick to point out that while the whole bypass shock thing has its roots in motorsport, the Old Man Emu range is not a competition product. “This is not a race shock,” ARB’s tech-team told us. “It uses race technology, but we’ve adapted it for everyday vehicles. It’s fully adjustable on the car and it’s application-specific; you buy it and bolt it in. It comes with everything you need as well as full instructions.

“We even include recommended adjustment settings depending on how you’re going to drive and what load you’re carrying.”

TJM’s new Pace shock absorbers are similarly set up for the vehicle at the factory and fine tuning for compression and rebound is done using the external eight-way adjuster.

Obviously, the more generic setup of the ARB, TJM and other mainstream product means you won’t get the absolute tailored performance of the real high-end stuff like King and Fox, but it’s still going to offer more performance than an OE replacement shock in the vast majority of cases.

Bump and rebound – what’s it all about

The external adjusters on bypass shocks vary the amount of bump and rebound control the shock itself provides, but what does that actually mean? Ask a bloke in the pub to define it and you could get all sorts of answers. So here’s the skinny from suspension guru Brett O’Brien of Shockworks on how it breaks down in the simplest of terms:

A shock absorber’s bump control is the force it applies to control the upward movement of the wheel and tyre. So, let’s say you’ve just clobbered a rock at speed, and that has started to compress the spring and sent the wheel heading for the upper limit of the suspension’s travel. The shock’s bump control is what stops the suspension arm (or axle) smashing into the bump-stop.

Rebound, then, is more or less the opposite and is the shock’s ability to control the movement of the wheel and tyre as it heads back down to its ‘normal’ position.

Generally speaking (and we mean very generally) more bump (it’s also called compression damping) damping will result in a firmer ride. Too much will make the ride too hard, while too much rebound damping can ruin ride as it allows the car to, as Brett puts it, “copy the road,” rather than iron out the bumps and lumps.

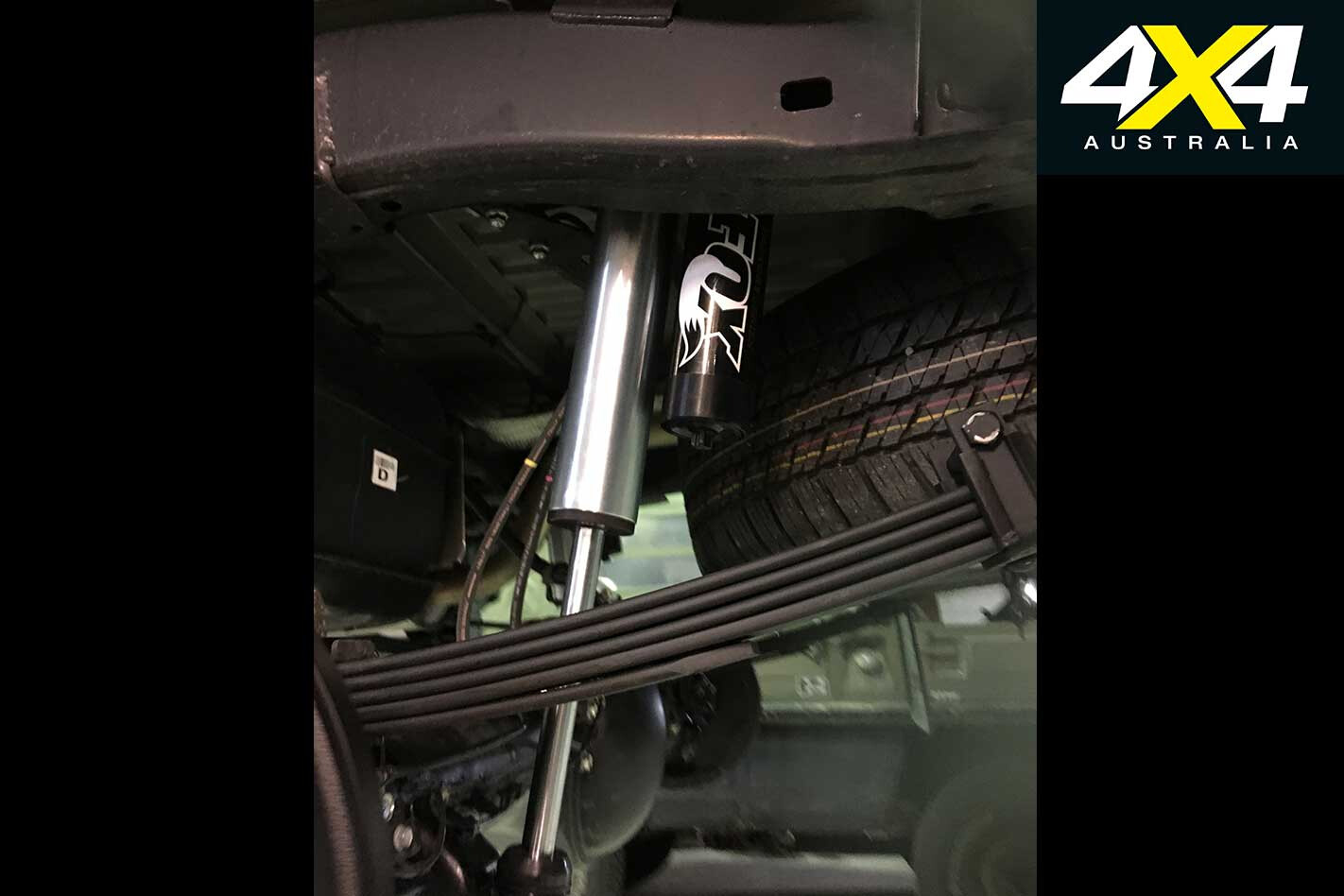

Not enough rebound is also a problem, particularly on off-roaders with big, heavy live axles, as it can allow for lots of body movement in response to the axles moving around without enough control.

Personality bypass

A conventional shock absorber’s behaviour is fundamentally a factor of the internal piston speed. But a bypass shock is constructed so that it also takes into account the position of the piston in the shock’s body (or tube). And that’s what gives the bypass shock the ability to behave like a vehicle with twin shocks on each corner.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of bypass shock, the external and internal bypass. Obviously, they’re constructed differently, but the aim is the same; that dual personality.

In the case of the internal bypass unit there are two main ways to arrive at the same result. In one type, there’s a conventional shim stack (which determines the bump and rebound damping characteristics) as well as a bypass stack. At low shock deflections some of the damping oil can travel through this bypass stack, allowing for a comfortable ride.

At larger deflections, however, a pin positioned internally at the top of the shock’s tube eventually mates with the shock piston and effectively closes the bypass stack, forcing all of the oil to pass through the shim stack, increasing the damping force.

In the other type, the shock body is more or less a tube inside a tube with ports allowing some of the fluid to bypass the main shim stack at small deflections, while the piston blocks these ports at higher deflections, forcing the fluid the hard way around.

The external bypass shock uses the same principle, but allows the damping fluid to bypass the shim pack, by being forced out into a series of external bypass tubes that are plumbed into the main shock body.

These external tubes are opened and closed by the movement of the shock piston in much the same way as the inlet and exhaust ports are opened by the piston of a two-stroke internal combustion engine. Vernier adjusters (usually a screw and lock-nut) allow you to tailor the bump and rebound damping by varying the capacity of the bypass chambers.

In the end, whichever way you choose to go, the advantages amount to a better ride over normal terrain, better damping in the rough stuff and the effect of having two different shocks to handle different conditions. Greater stability at high speeds is the big bonus for competition vehicles using bypass technology.

Ultimately, the reality is that the bypass shock was the solution to the problem of having variable suspension spring rates and requiring a variable damping rate to cope with that.