IT’S one of, if not the toughest vehicle trek in Australia.

This article was first published in 4×4 Australia’s November 2011 issue.

Covering 1700-odd kilometres of sandy tracks, sharp rocks, soft dunes, vicious corrugations that murder shock absorbers, and tyre-shredding mulga, the Canning is tailor-made to be hard on vehicles. And it’s all in one of the remotest parts of the country, where your nearest medical service could be half a day away and mechanical repairs even more distant.

Out here you may not cross paths with another traveller for days. Yet, each year hundreds of Australians and many international travellers take to the Canning Stock Route in their 4X4, seeking adventure, experience and solitude. The CSR is on many a 4X4 enthusiast’s list of must-do tracks, but the sheer length of it, its remoteness, and harshness put it out of reach for many.

Just getting there from the East Coast entails a week of outback travel. Taking a vehicle to the Canning requires special preparation: all-terrain tyres at the very least, preferably light-truck construction; heavy-duty suspension; the ability to carry huge amounts fuel and water; and supplies for at least two weeks of remote travel.

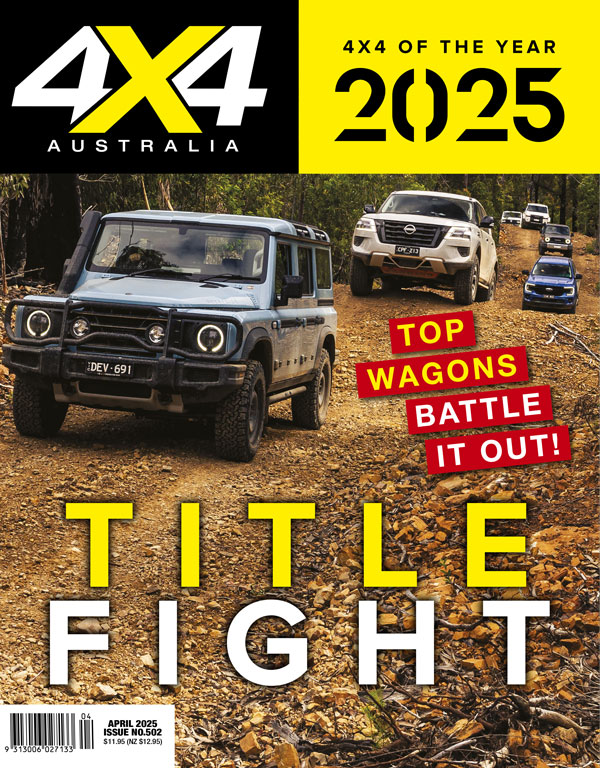

Heavily kitted-out Toyotas, Nissans and the odd Land Rover are the vehicles of choice out here, so why would anyone attempt to take on the CSR in a showroom-stock vehicle, let alone one wearing the three-pointed star of Mercedes-Benz?

Benz brought its G-Class wagon back to Australia earlier this year, and it was with five G 350 Bluetec wagons that a select group of journalists from Australia and Europe set off from the southern end of the route at Wiluna. They were supported by two G-Class Professional vehicles, one a wagon and the other a 4.5-tonne flat-bed ute.

The G-Professionals are heavy-duty G-Wagen variants and similar to the vehicles recently purchased by the Australian Defence Force. To be totally honest, the G 350s were not completely stock.

The highway-oriented standard tyres were replaced with more rugged Yokohama AT-S rubber; roof racks were fitted to carry tents, equipment and spares; some vehicles had their rear seats removed and fridges fitted – but that’s it! The suspension and mechanicals were totally stock standard.

There were two Mercedes-Benz technicians who came along to clean air filters and attend to any mechanical maladies, expected or not. The spares they carried included Canning ‘essentials’, including shock absorbers, tyres, filters and tools. Not so usual was the factory diagnostic computer also in the kit.

One of the techs was Erwin Wonisch. Considered to be the ‘godfather’ of the G-Class, he has been working on the iconic Benz for more than 32 years. Even since its pre-launch engineering stage, in fact. Erwin was last in Australia for the launch of the G-Class in Tasmania and said he wouldn’t have missed the opportunity to experience the outback at its toughest.

“This has been a great adventure,” said Erwin mid-way through the trek. “I have driven the deserts in Africa and Algeria, but they are nothing like the desert here. The distances are huge! You would have to do laps around Saudi to go this far. The changes in the desert are amazing and it has been a real test for the G-Wagen. Australia is a big country.”

Accompanying Erwin was Luke Pascoe, an M-B technical specialist at Benz HQ in Melbourne. Together they worked like the odd couple as they took care of all the maintenance and vehicle checks. They made up the six-person logistics team on the trek, which included a trauma specialist doctor and two paramedics.

Some people take a month or more to drive the full 1619km of the CSR from Wiluna to Billiluna, stopping to see each of the 51 wells dug by Alfred Canning and his construction party in 1908-09, as well as taking detours to visit the natural wonders along the route.

However, the M-B party had set itself a tougher deadline. Their goal was to cover the route in just 12 days, including the extra 170km from Billiluna to Halls Creek on the Tanami Road. Leaving Wiluna around lunchtime, the target was Well 6. It didn’t take long for us to settle into the rhythm of the road and the dust and bumps.

As the track narrowed to single vehicle width, the Europeans soon forgot they were driving on the ‘wrong’ side of the road, even if they were driving on the right-hand side of the vehicles. The first of Canning’s wells to pass was Well 2, with nothing much to see but an old windmill and an overgrown hole in the ground.

Well 2A was just 35km further up the track and, although not built on the original construction trip (but on the return journey in 1910), it’s unique in that it is bored in solid rock, hence its name, The Granites. Through this early part of the route the track is relatively flat, but rutted and rocky.

It passes through private property on Cunyu Station as it bypasses some nearby lakes. This made for slow going in the Benzes and the sun was fading into an orange glow on the western horizon before Well 6 was reached, so camp was made at Windich Springs, also known as Well 4A.

The route continues to be flat and rocky north from Windich Spring, but away to the west the Carnarvon Range shows how diverse the terrain is in the central part of Western Australia. Well 6 was the first restored well we came across, and the Geraldton 4WD Club did this work back in the 1990s.

Although the red sand and spinifex are ever-present, the country is constantly changing. Aerodrome Lake provided the first look at a dry salt lake and small sand dunes started to become a feature. As tempting as it is to tear out across the flat expanse of the salt, these dry lakes are a trap for vehicles – they can easily break through the crust and become bogged up to their axles.

With nothing to provide a winch anchor, recovering a vehicle from the salt lakes can be a long and arduous task, so it’s best to stay off the surface. The formed track skirts the edge of the lake and, despite the off-road abilities of the G 350, we kept to it.

The G was proving to be a fine vehicle for this sort of travel. We had commented in earlier road tests that the suspension was too firm, but this was in an unladen vehicle. Loaded with a fortnight’s gear, they rode much smoother on the track and coped well with the weight even if you are reminded of the extra gear up on the rack each time the track takes a sharp turn.

As interesting as the passing terrain is, the track demands the full attention of the driver. Slow and steady is the way to pass safely, as there’s always a sharp turn, or washed-out rut, to catch you off guard and possibly damage the vehicle, or worse.

We found the easiest way to drive the G on the tracks was in high-range and to keep the centre diff locked. This allowed a good pace on the open stretches and when approaching a sand hill it was simply a matter of tapping the conveniently located button to lock the rear diff, and possibly the front diff as well, depending on the size of the dune and the condition of its approach.

The G 350s were showing no signs of trouble on the first days of the trip. We had the first tyre puncture on day one and, after fitting the spare on the track, Erwin and Luke replaced the damaged tyre on the rim in camp that night.

When punctures over the following days were on the same vehicle and always on the left-hand rear tyre, we began to suspect that the Europeans were driving too far to the left of the track and in the rocks and mulga. Our suspicions were confirmed when one of the Germans swiped the left-side rear-view mirror off the car.

Considering that the CSR passes through three deserts, the Little Sandy Desert on this early part of the route, there is a lot of vegetation along the track and in places it towered over the vehicles and whipped along the sides. The exterior mirrors copped a hiding and the scratch-resistant paint Mercedes applies to its SUVs was put to the test.

The terrain changes again on day three as the convoy skirts the Durba Hills to the east of the CSR. The rocky outcrops provide a sharp contrast to the sandy flatlands we’d been traversing to date and contain several spectacular gorges, natural springs and Aboriginal rock art.

The Calvert Range is further east again and said to be a worthwhile detour on any CSR trek, but with a schedule to stick to and the chance of a dip in the pools at Durba Spring, our convoy rolled on in to the gorge housing this natural spring near Well 17.

Durba Spring hasn’t flowed for some years and the murky waterhole was in the shade of the rocky escarpment so it didn’t entice any swimmers, regardless of how dusty we were. The area would be an ideal place to camp and rest after a few days on the track.

It’s in a grassy valley between the cliffs and there are Aboriginal petroglyphs on the surrounding rocks. Instead of setting up an early camp, we lunched at Durba and moved on to Well 18, a dusty campsite out on the plains. This was the first time we shared a campsite with other travellers.

The well provided clean water and we were able to top up our washing supplies. The organisers of the trip provided a satellite dish that was set up each night to give Wi-Fi internet connection for the journalists who had to send stories back to their offices daily.

On this night it was used to watch the F1 Grand Prix. Who says you need to go without in the outback? More contrasts on day four as we crossed the Tropic of Capricorn, just south of Well 19, and caught our first glimpse of Lake Disappointment to the east.

There are a few dry claypans to cross as you head north and one of these opens up to reveal Savory Creek, which is likely to be the only creek you will cross on the CSR that contains water. It is very salty, so don’t linger in it in your vehicle. The track heads east along the southern bank of the creek before crossing it at a point where it was fairly narrow on our visit.

The creek widens again as you follow it east toward the lake and the reddish bushes that carpet its banks make a spectacular sight among the sand ridges. Lake Disappointment is a massive salt lake that is mainly dry.

There is a track that continues east around the edge of the lake and, like the other salt lakes, you are best to keep off the surface itself as it can be treacherously boggy. The main track heads north from the lake past Wells 21 and 22 to the junction with the Talawana Track.

Near the junction is Georgia Bore where clean, refreshing water can be pumped up using a hand pump. With the fresh water and a composting toilet here, Georgia Bore is a popular campsite and there were many people camped there when we pulled in for lunch.

One party was busy replacing broken springs under the rear of their ute. The Talawana Track signals your entry to the Gibson Desert. It heads west towards Newman and takes you past Australia’s most remote national park at Rudall River. One of the many constraints of travelling the Canning is fuel use and the lack of any supply along the route.

You can buy it at the start and finish at Wiluna and Billiluna, and it is available at the Kunawarritji community near Well 33. Kunawarritji is around 1017km from Wiluna, and a little more than 600km from Billiluna; that’s not including any detours you make, so you’ll want enough fuel for at least 1200km of tough, sandy four-wheel driving.

There is another option with a fuel drop available at Well 23 near Georgia Bore, about 715km north of Wiluna. Fuel is brought in from the Capricorn Roadhouse near Newman via the Talawana Track, and is delivered to a marked spot alongside the CSR in 200-litre drums.

The fuel needs to be ordered a month in advance by calling the roadhouse. The price for the fuel drop on this trip worked out to just less than $3 per litre, delivered, which is reasonable considering what it takes to get it there. Fuelled up, we moved on to Well 24 for our camp.

A mid-morning break on day five at Well 26 allowed for a welcome wash. For some on the trip, a shower was well overdue and the fresh cool water couldn’t have felt better. Well 26 was restored in 1983 and is probably in the best condition of all the wells along the route. Rocky mesas and big sand dunes kept the track interesting as we continued north.

Along here, we passed several large convoys of 4X4s heading south and a lone cyclist from Holland who was doing the entire route. Camp was different again and we set up near Well 30 among a stand of bloodwoods that were teaming with budgerigars.

The track levels out somewhat between wells 30 and 33 and, as with every other time it does so, the corrugations became more evident.

Along the final 30 or so kilometres before reaching the intersection with the Wapet Road (which heads west to Port Headland on the coast) and the Jenkins Track (which becomes the Gary Junction Highway and heads east to Alice Springs), the corrugations have become so fierce that an extra track runs alongside the main track to try and avoid the worst of them.

The smooth, wide expanse of the Wapet Road felt like a freeway after the corrugations of the CSR. It’s just 10km west on the Wapet before you reach the community of Kunawarritji, where we could fuel up the vehicles and reorganise the loads to prepare for the second leg of the trip.

After the harsh pounding the G 350s had just copped, it was no surprise to find a left-rear shock leaking on one of the vehicles driven by the Germans, incidentally, the same one that received most of the tyre punctures.

We didn’t think too much of it, as Erwin and Luke replaced it during a check over of all the vehicles while we over-nighted in the excellent new accommodation at the community. Well 33 also has the only major airstrip on the CSR, and it was here that our new German friends left us and a fresh crew, including two Brits, a single German and a few Aussies arrived.

They were all keen to hit the track and experience the G-Class on the Canning Stock Route. Little did they realise that they would experience just how tough the track can be.