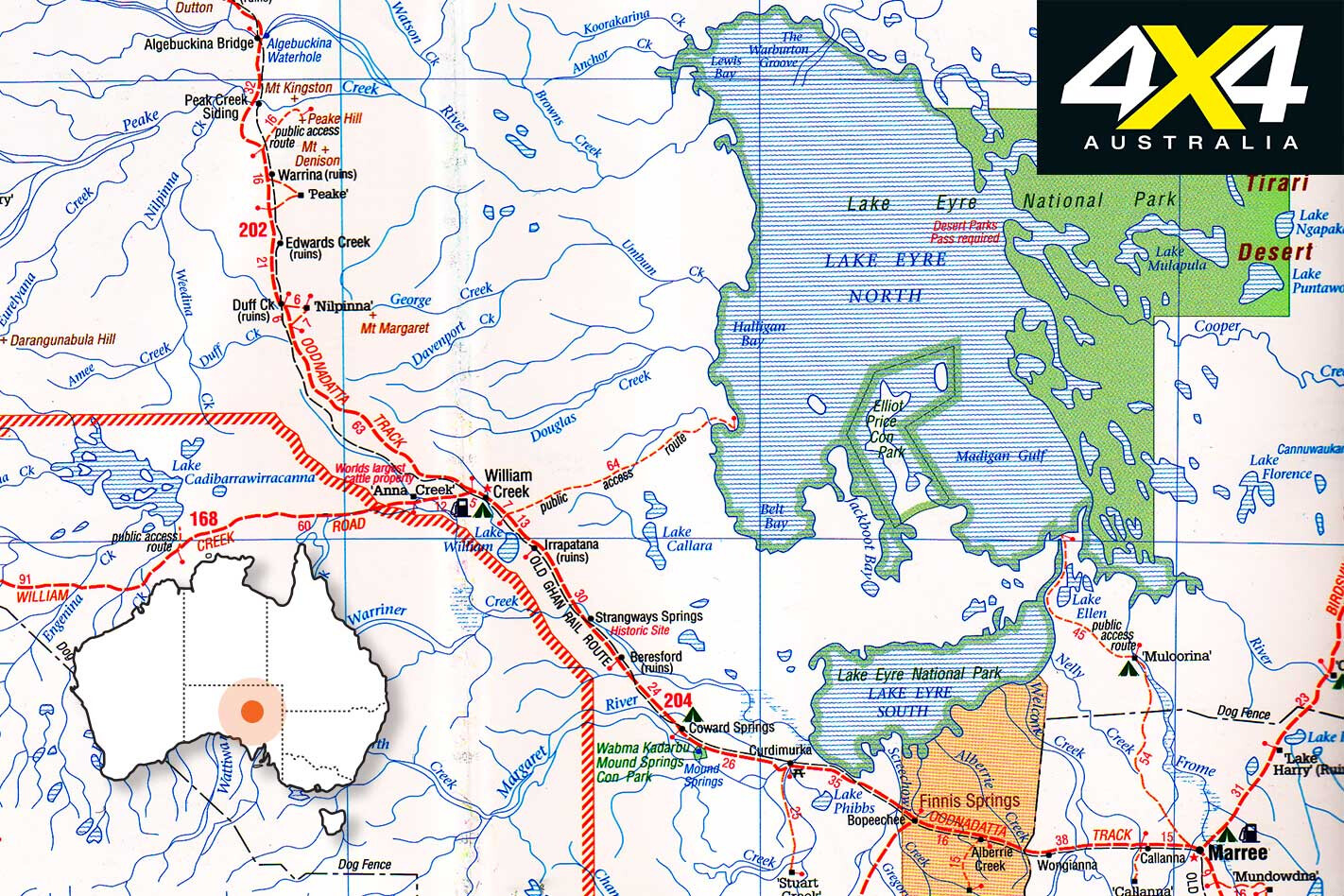

The sense of remoteness is tangible as you travel north-west from Marree, a small, isolated outpost on the edge of the driest and harshest country you’ll find in Australia, 380km north of Port Augusta in the bleached outback of South Australia.

This article was originally published in 4×4 Australia’s February 2011 issue.

But for a fluke of geology, few people would come this way and history as we know it would not have been written.

Dotting this country in a great arc from near Lake Callabonna, north-east of present day Arkaroola in the Flinders Ranges, through Marree to north of Oodnadatta, is a series of so-called mound springs.

These springs, where ancient water (some say over a million years old) bubbles up to a parched land and transforms it, were the basis for the ancient Aboriginal trade routes that crisscrossed the dry heart of Australia. When Europeans started exploring this country, those same mound springs were the key to the centre and beyond.

The mounds were first discovered by Major Peter Warburton in 1858. John McDouall Stuart, arguably Australia’s greatest explorer, used the springs as stepping stones to the interior and for his successful crossing of the continent in 1862. Pioneer pastoralists followed, quickly taking up the land around each and every spring.

Stuart’s route was so practical that 10 years later, when the Overland Telegraph Line (OTL) was pushed through from Darwin to Adelaide, it followed virtually the same track across the continent. With the OTL as a safe and known line on an otherwise blank map, other explorers set out from its repeater stations into the vast western interior.

Then, as the railway was pushed north from Port Augusta, it too followed Stuart’s route, reaching Marree, originally known as Hergott Springs, in 1884. Oodnadatta was then connected to the railway in 1890, but there the railhead stayed until it was finally pushed through to Alice Springs in 1928.

The track that sprang up beside the OTL was tramped by budding explorers, pioneer pastoralists (my great grandfather among them), Afghan cameleers, itinerant workers, missionaries and early adventurers. The steam trains that followed the route were almost entirely dependent on the waters of the mound springs and the occasional artesian bore dug along the way.

Today when you travel the route you are rarely out of sight of the old Ghan Railway Line, and often you come to the scattered ruins of the OTL. Here and there are other iconic features of our arid inland; an ephemeral water-covered Lake Eyre, the oasis of Algebuckina Waterhole and the nearby historic bridge of the same name that spans the sometimes mighty Neales River.

The Oodnadatta Track is more like a good dirt road these days, its only challenge being a wayward rock that can easily tear the sidewall out of a tyre, or after heavy rain when the creeks wash across the road and the track becomes, for a short time at least, a set of wheel marks vanishing into the distance.

The rewards for travelling are many. The sense of history is palpable, the vastness succour for the soul, while the characters you meet, like the commodore of the Lake Eyre Yacht Club, are more than memorable.

Then there are the harsh natural wonders of the region, the mound springs and Lake Eyre among them, while the quirky places along the route, such as the ‘artistic’ sculptures just north of Marree, the rustic interior of the William Creek Hotel, or the gaudy exterior of the Pink Roadhouse, say more about the Australian psyche than any encyclopaedia on the subject!

Travel Planner

START Marree

FINISH Oodnadatta

LENGTH 405km

LONGEST DISTANCE WITHOUT FUEL 204km between Marree and William Creek

BEST TIME TO TRAVEL March to September

More info marree.com.au williamcreekhotel.net.au pinkroadhouse.com.au lakeeyreyc.com www.wrightsair.com.au environment.sa.gov.au