Sometimes it takes remnants like great, rounded boulders in a deep gorge to signify that occasionally, water inundates what seems to be a dry, desiccated landscape. When those floods come, whether as gentle flows, or violent torrents, we should grab the chance to see it ourselves.

This feature was originally published in 4×4 Australia’s December 2012 issue

With this in mind, my wife Jan and I load the camper-trailer and head west out of Sydney’s urban sprawl towards a million square kilometres of dry red dirt, sand, corrugations and bulldust. After an overnight stop in Forbes, in central-western NSW, we make the 900km haul to Broken Hill.

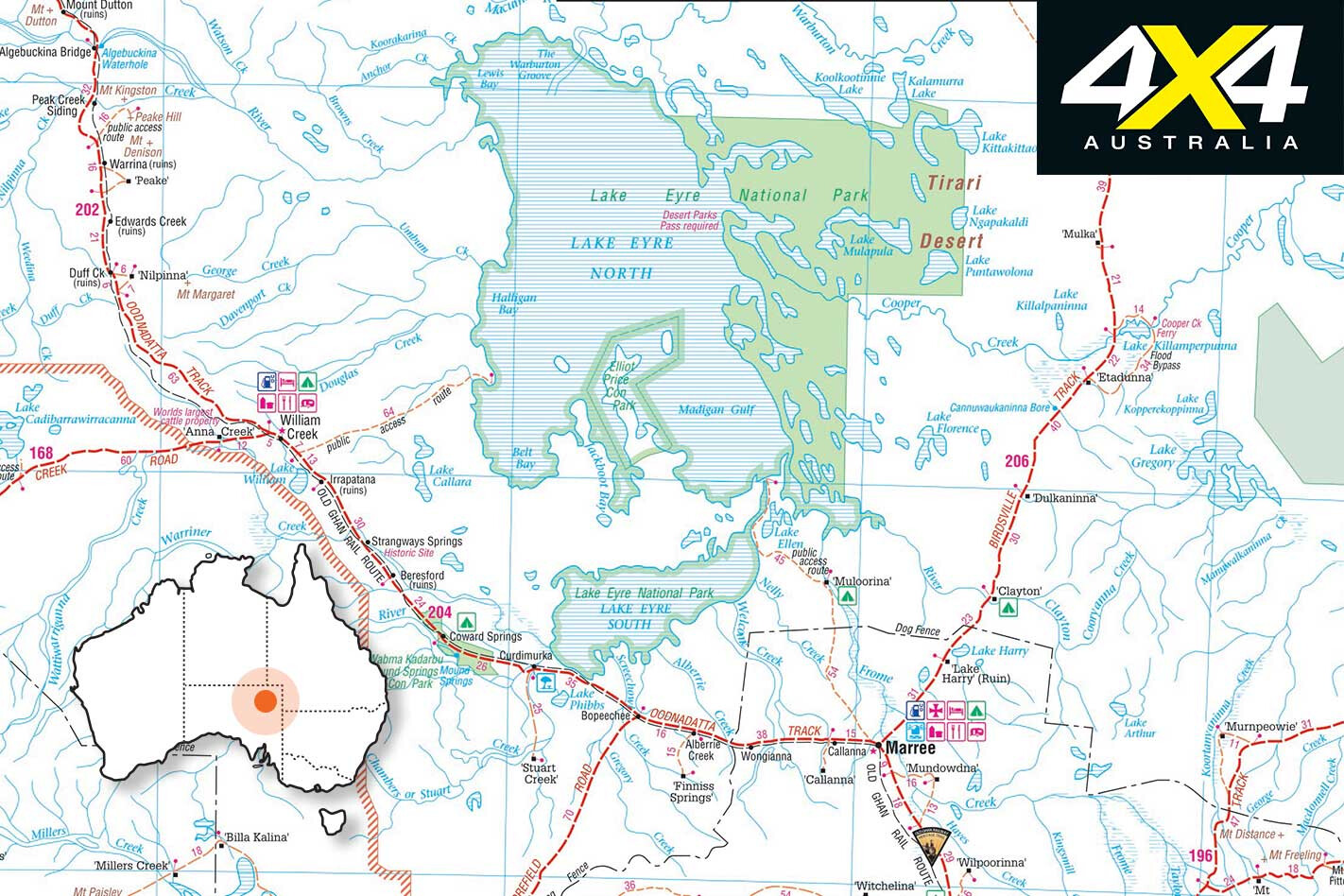

We reach the edge of the great Lake Eyre Basin, one of the world’s largest internally draining freshwater systems, covering 1.2 million km² – nearly one-sixth of the nation’s landmass. The next day, we continue west towards South Australia, plunging over the basin’s edge, where all streams now flow north-west towards the great lake.

The next day’s trip north, through Parachilna, Leigh Creek (for provisions), Marree and onto William Creek is a mostly easy 450km and gives us our first glimpse of water in south Lake Eyre from the trackside viewing area. When there’s water in this part of the lake, you know it’s nearly full.

We roll into William Creek at sunset, amazed at the growth in what had been a tiny settlement the last time we were here, six years ago. It’s still small, but gone are the old lights which controlled ‘traffic,’ allowing planes to taxi off the dirt airfield up to the pub. Now, there is asphalt on the landing strip, and a line of aircraft waiting to fly eager trippers out over the waters of the lake, 40km away.

The campground, once a bare strip of gibbers and sand, is packed with campers and lots of booked-out, transportable accommodation.

Here, we meet our friends from Adelaide, Phil and Lyn Pullem, who have the advantage of a plane – a two-seater CZAW SportCruiser. With most of the territory around Lake Eyre isolated, this is the best way to admire the immensity of the flooding, which we experience the next morning as we fly east over the sandhills and the gibbers.

The scope of Lake Eyre can really only be appreciated when it’s full of water, but by the time we reach it (in September 2011) it’s a little down on its peak. Still, it’s an awe-inspiring sight as we fly in at high altitude, with water stretching almost to the horizon.

At times, it’s easy to forget where we are. Concentric rings of salt around the lake’s perimeter mark earlier highs and give way to the gentle greens and olives of the lake’s water, lapping around Belt Bay, Silcrete Island, Babbage Peninsula and Jackboot Bay. We might as well be cruising up the coast somewhere, not dodging updrafts in the heart of a desert.

On the eastern shore, the whole make-up of the lake changes. Pure pink rings line the bottom, produced by beta-carotene pigments from algae in the sediments. This continues right up the eastern shoreline until we reach the inflow of waters from the Cooper, one of the great arteries pouring life into the lake. After several circles of this area we turn back south-west, towards William Creek.

We spend several days at William Creek, before waving our friends home from the airstrip perimeter. After fuelling up – at $2.20 per litre – we turn back south, along the Oodnadatta Track, retracing our tracks. This time, we turn left off the track 7km from town to Halligan Bay, to camp on the lake’s edge.

A sternly worded sign on the way in reads: “This is a track, not a road” and warns that the track is not regularly maintained.

These potential safety issues are underlined as we pass a memorial for Caroline Grossmueller, the Austrian tourist who died here in December 1998. She had ignored advice to stay with her bogged vehicle, and had been overwhelmed by the harshness of the outback summer. Her body was discovered on December 17 – she reportedly had seven litres of water in two containers beside her.

On arrival we set up camp, then don gum boots, grab our cameras and begin a 100m walk across the mud to the water’s edge. Jan is disappointed by the lack of birds, with just a handful of gulls and one flock of pelicans flying over us. It seems the abundance of water this year means there is no need for them to travel this far inland.

We figure this will be a campsite that we’ll have to ourselves, but over the afternoon a steady stream of travellers arrive. A few stop just to snap photos, whereas others find a spot to camp – the preferred site just short of the defined camp area, from where the lake itself can be seen.

The next morning we are back on the way to the Oodnadatta Track and, yes, the sign was right; the Halligan Bay track is not often maintained and travellers have forged their own tracks to avoid the worst of the bulldust and corrugations.

We also stop at the ruins at Irrapatana, the old Overland Telegraph settlement at Strangways, Beresford train station and several of the Old Ghan Railway bridges before pulling into Coward Springs for our night camp. The warm waters of the spring are a welcome reviver after two days of hot and dusty conditions and the facilities, including the wood-fired water heater, are excellent.

It’s day nine as we head out in the morning, eager to inspect a few of the mound springs along the track, including Bubbler and Blanche Cup. These valuable water resources kept early explorers and cattle drovers alive in the 19th century, but many have now dried up as water pressure in the Great Artesian Basin has dropped following extensive drilling of bores.

At one point, we become bogged on a sandhill while driving off the track but soon dig ourselves out and are back onto the made surface and the strange wonders of Planehenge lead us into Marree. After a cold beer in an old pub, a fuel reload and stocking up on fresh provisions, we head north-east on the Birdsville Track.

Part of the appeal of this trip is to see where the flooding waters finish up in Lake Eyre, how it gets there and the impact it has along the way. The Birdsville Track and south-western Queensland offer many opportunities to see this, at places where the waters intersect tracks and roads.

The morning of day 10 takes us north from Clayton Station (54km north of Marree), across the Strzelecki Desert, past Dulkaninna and then down the turn-off at Etadunna onto the bypass track to take the ferry across the Cooper.

Two weeks earlier, following the end of the annual Birdsville races, there had been a 23-hour wait to get onto the punt, with travellers erecting tents on the track, setting up barbecues and enjoying a party as they awaited their turn. It set a new daily record of 111 vehicles, which was proudly scrawled on a piece of cardboard cable and tied to the frame of the ferry.

We have no delays and drive virtually straight on, then turn off to a parking spot on the northern side of the Cooper. Here, we marvel at this stream of emerald-green water flowing across the desolate tract between sandhills and over gibbers.

We drive down a winding track along the side of the 200m-wide stream, admiring the birdlife and taking in the extent of this water. It’s a steady, broad sheet of green water, quite fresh, if a bit earthy to taste.

Another 75km up the track, across the gibbers of the Tirari Desert, we stop at Mungerannie Roadhouse. It’s early afternoon and we get our choice of campsites and pick a narrow slot among the scrub bordering the wetlands. Just metres from the door to our camper will be a spreading sheet of water, with spoonbills, ducks, egrets, herons, swamp hens and black kites making the most of this oasis in a dry land.

However, as we are backing in, Jan notes an unusual sound from one wheel on the trailer and it quickly becomes apparent that we have a bearing problem. Over the next hour I remove and replace the failing bearing. Had we pushed on for Birdsville or somewhere further up the track, this would have been a real mess. We’ve caught it just in time.

After dawn on day 11, we hit the track again, across Sturt’s Stony Desert and over the sandhills on the edges of the Strzelecki and Simpson deserts and across the bird-rich, milky waters of the Diamantina River into Birdsville. What was once a true outback village is slowly urbanising, with new civic buildings, semi-urban developments, asphalt roads and creature comforts of civilisation. Even the Birdsville Bakery is now in a shiny new edifice, though the curried camel pies and lamb shank pies are just as tasty.

Heading south-east on day 13, we reach Quilpie, then cross Kyabra Creek and the Bulloo River before checking into Thargomindah’s camping ground.

This was one of the first places in the world – after London and Paris – to provide hydroelectric power for electric lighting, tapping subterranean heat for power. We check out an afternoon demonstration of this at the old power station – rumoured to be the oldest in the world.

On day 14, we head east to the opal mining town of Eulo, with an estimated population of “50 people and 1500 lizards”. We think they underestimated the lizards. Here, we get a glimpse of the narrow grasp some of these small towns have on survival, as the local store had burnt down two months earlier. Residents now drive 70km to buy food and fuel at Cunnamulla.

After a brief stop we traverse the Paroo River. Not far from the “mud volcanoes”, where gooey sediment from the edge of the Great Artesian Basin erupts through the surface, we turn south on the Dowling Track towards our next destination – Currawinya National Park.

This old sheep station is now a sanctuary for the bilby reintroduction into western Queensland, and for those seeking to experience the natural world in this rich semi-desert country.

The next day we head off to inspect The Granites, a poor man’s Devils Marbles, and then go on to the freshwater Lake Numalla and the saltwater Lake Wyara. While the former is nice but bare, the latter is a crowded multitude of pelicans. They spiral upwards on the thermals, and swarm noisily into the air at our approach.

Despite a local pub owner warning us the roads could be unsettling, we actually don’t find the next 220km to Bourke too unpleasant. But as we cross through that border gate into NSW, the watershed changes from the point where the rivers flowed north and west, and curves into the mighty Lake Eyre Basin, to where the creeks and rivers begin flowing south, towards the Darling. It is from here the water ultimately drains out into the Southern Ocean, almost 3000km away.

As we cross the deep channel of the Darling at Bourke, a modern highway overpass, skirting the charm of the old bridge alongside it, underlines our change of drainage basin. We travel another 90km west to Brewarrina and then 8km out of town we bear north-west for the 160km trip to Goodooga on what is the best dirt road we’ve ever seen.

A further 35km south-east takes us to the Castlereagh Highway and after another 28km, we swing into Lightning Ridge. Unlike other opal mining centres, Lightning Ridge is where all old trams, train carriages, car doors and cement mixers go to die.

There’s relatively little life underground, other than in the mines, but lots of ramshackle dwellings among the scrub. The one thing the Ridge does share with all other opal centres is the eccentric people it attracts, making it a must-see.

As we headed back home, we reflected on what we’ve learnt along the way – mainly that rain isn’t just a nuisance, but rather, part of nature, vital to our existence.

The Price of Pleasure

There’s a price to be paid for the pleasure of following our dreams with a 4X4 and camper-trailer.

Over a total of 21 days, we clocked up 6235km and used $1697 worth of fuel. Aside from the food we left home with, we consumed $658.30 in food and drink, which included the occasional ice cream and beer in outback pubs.

Camping fees cost us $317.60; broken down, this was a rate of about $10-$30 per night. These ranged from commercial camping areas – usually when we needed a shower and washing and wanted to tap into 240 volts for the night – to national parks.

Despite enjoying the facilities and resources in several national parks, there were no park entry fees. One (Clayton Wetlands) was on an honour system and we put $10 into the box.

We also had $104.90 in miscellaneous costs (a replacement wheel bearing, several loads of washing, a phone card for use in areas that were outside mobile range, etc.). In addition to this, we bought a full Desert Parks Pass ($143) before we left to ensure access to all our planned destinations in South Australia.

That’s a total cost of $2930.80, which these days isn’t too bad for a three-week holiday for two people. It equates to a touch over $900 per week, including all food, accommodation and travel.

Given the wonderful and once-in-a-lifetime experiences, we thought it money well spent.