WE TURNED off the road onto what was not much more than a couple of wheel marks across the bare sand. As we got closer to our planned destination I scanned ahead, keenly looking for the object of our desires. A red dune blocked our way with the two wheel marks heading over it, while the Hema Navigator was indicating the spot we were searching for was before the dune crossing; but I was darned if I could see it.

Willie Rockhole appeared suddenly and almost unexpectedly on the bare plain we had been travelling across. I was anticipating a pile or small hill of natural rock where a rock hole or, more correctly, a gnamma hole, would be found somewhere on its surface.

Willie Rockhole was different to that, with the flat rock surface almost completely buried under a veneer of red sand which, on closer inspection, proved to cover quite an area and formed quite a large catchment for the gnamma holes that collected the precious water. Only one of the three rockholes here had water in it, though, and that was the smallest of the group. The largest one, although nearly filled with sand, had wet sand once you dug down a little; and more water could have been obtained, I’m sure.

Later that day I found another gnamma hole, this one on a low hill of rock where a rock lid, or cap stone, could be dragged across the cavity to stop the precious liquid from evaporating so quickly in this dry desert climate.

These isolated treasures were the lifeblood for the wandering bands of local Aboriginal people, their location told in stories handed down over generations. Later, explorers and pioneer graziers relied on them for their journeys of discovery, while today nearly all are unused and forgotten about.

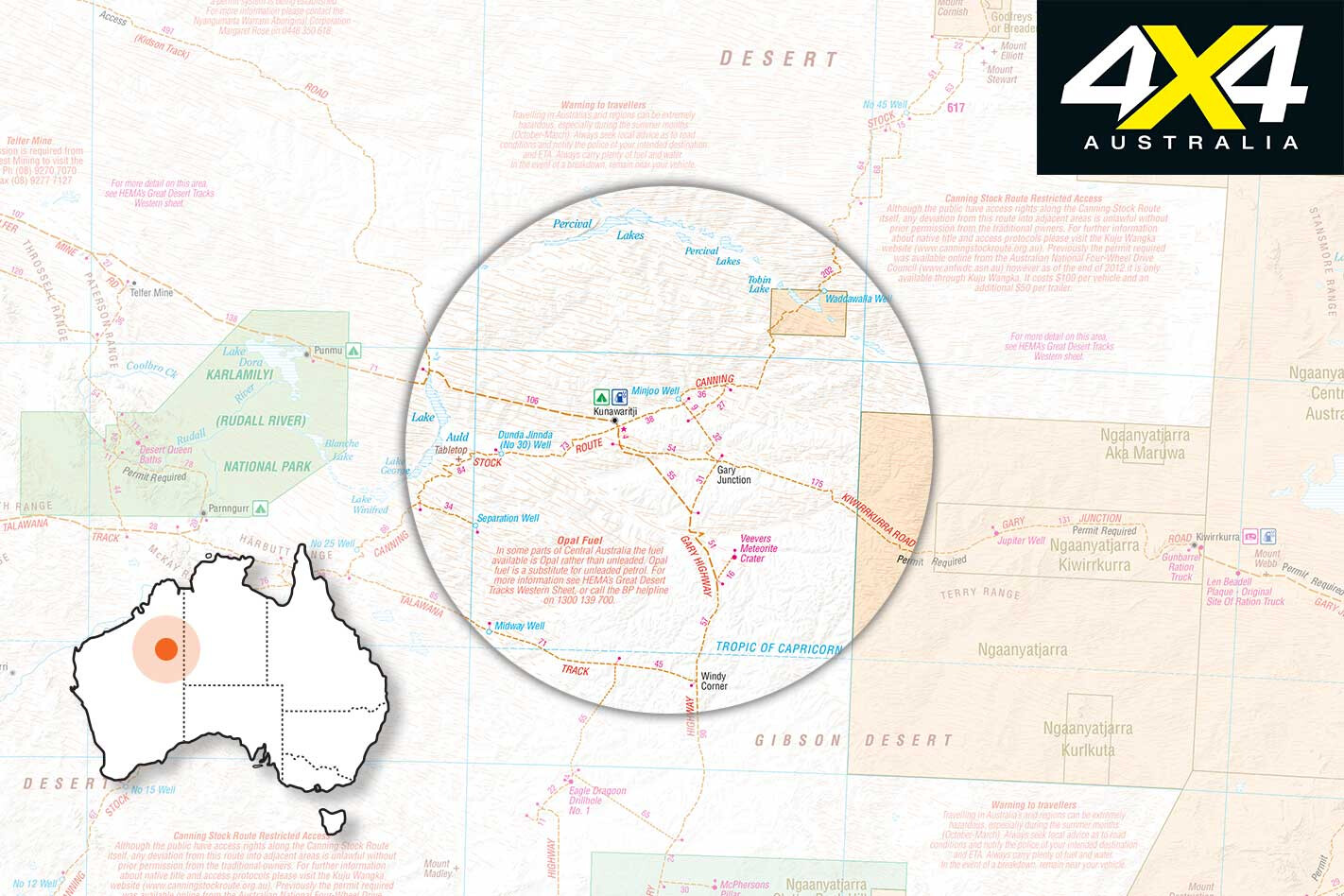

We’d left Marble Bar a week earlier, heading east on the blacktop of Ripon Hills Road. Intrigued by the sign of the Meentheena Veterans Retreat, about 80km east of the Bar and before you cross the Nullagine River, we turned south to check this area out.

Now part of the Meentheena Conservation Park which covers 290,000ha, the retreat is a well-established camp set up for veterans and located about 6km south of the main road. Here you’ll find camping and powered sites, some accommodation, a great camp kitchen, toilets and showers, and the camp host.

For those who can’t be disconnected from the modern world, an internet connection is available. Not far away and spread along the Nullagine River are a number of delightful campsites, with camping just $15 per night.

There are a number of places to enjoy in the reserve and, with a map from the caretaker, you can visit the original homestead, historic graves, old mine sites, once-important telegraph stations, large, dry sinkholes and caves, as well as the many stretches of water spread along the Nullagine River. It is well worth a visit and is nowhere near as crowded as the more well-known and frequented Carawine Gorge, which is less than 20km away as the crow flies, but a bit farther by road.

Not much farther east the bitumen swings south to Woodie Woodie (and Carawine Gorge), while the route we wanted to take – the wide and very dusty Telfer Mine road – continues east, winding through the Gregory Range. Once through the rugged range we were into low red dunes and the western margin of the Great Sandy Desert.

The track to reach the highlights of the Rudall River NP branches off to the south further eastward, while the mine road swings a little north to skirt around the great open cut, portions of which are visible for the observant traveller. One of the biggest, most productive gold mines in Australia, the surrounding area also produced copper and more gold from other, albeit smaller, workings.

That evening we pulled up on the northern edge of the large saltpan of Lake Dora, which lies within the national park and occasionally gets water from the rarely flowing Rudall River. A family of dingoes were nearby, their den, as I found later, tucked in beneath a patch of thick green bushes and surrounded by a dense curl of spinifex.

The next day we rolled into the small hamlet of Punmu, which is an important but small Martu Aboriginal community; their country taking in much of the Great Sandy Desert region we were travelling across. We couldn’t find anybody to get fuel (maybe we were too early in the morning), so we headed back out the short distance and continued east along the main road.

Stopping for a yarn with a grader driver, we learned he was part of a team of maintenance workers looking after the road on the WA side of the border. Spending three to four weeks at a time there, he returns to Broome for a couple of weeks before doing it all over again. I got the impression he prefers being out in the desert country than in the trendy tourist port.

We pushed on, the route taking us around the top of Lake Auld before striking east again and arriving at the Aboriginal community of Kunawarritji at around lunchtime with everything closed. The Canning Stock Route is crossed just east of the village, and we headed up the track a short distance to set up camp at Well 33. Water cascades here from a water tank, which is fed by a slowly spinning windmill; the water forming a small pool, albeit larger than it was when we last visited here 10 years ago.

With camp set up, we cruised back into the community and met the couple who ran the store, organised the ranger programme and looked after the health clinic. This is again mainly a Martu community of about 120 people, with the population varying from a hardy dozen or less during the baking summer to more than 200 if some important business is being discussed. The main community living area is out-of-bounds to most visitors, and the once-vibrant art centre closed; so we took on some fuel and a couple of ice creams and headed back to camp.

The next day we stopped at Gary Junction, where you’ll find one of Len Beadell’s plaques. Len was in charge of the Gunbarrel Road Construction Party (GRCP) that built many of the roads in this vast desert region during the 1950s and ’60s. An avid story teller, he wrote a number of books and his legacy and the tracks he made are used by hundreds of four-wheel drivers every year. You can find out more about this great bloke and his roads at: www.lenbeadell.com.au

A couple of hundred kilometres east we pulled up at Jupiter Well, probably the only marked camping spot on the entire route. While Len and the GRCP had bulldozed the Gary Junction Road in late 1960, the original water point (which is about 150m south of the road) was dug by a National Mapping survey crew in August 1961. That evening one of the surveyors noticed a reflection of Jupiter in the waters of the new well, hence its name.

We found a couple of friends of ours who were heading in the opposite direction, camped beneath a tree; so after the obligatory welcomes, handshakes and swapping track conditions with one another, we had a few beers around the campfire. It’s a pleasant camp (on the north side of the road) surrounded by stately desert oaks, while the new hand pump delivers beautiful fresh water for travellers to enjoy.

Sadly, someone had recently buried rubbish and a dingo had dug it up, spreading the paper, plastic and rotten vegetables all around. I’m unsure why people don’t burn their rubbish and carry the stuff that can’t burn out with them? Laziness, probably.

The next day we passed a few more Len Beadell markers and wound our way through the Pollock Hills, before taking the short diversion into the Kiwirrkurra Aboriginal community for a sip of fuel and to check out the well-stocked store.

On the edge of the township near the water tower, Len’s old ration truck sits behind a low fence, while a nearby plaque tells its sad story of being burnt out during a long-distance towing operation. Of course, Len’s yarn about it in one of his books is much more dramatic, with a twist or two of Aussie humour thrown in to make it all the more readable.

The road continued as before, with a few short sections of minor corrugations to remind you that you were on a dirt road. Passing through the Dovers Hills, Mt Tietkens amongst the Buck Hills came into view a short distance farther on and we pulled up for the evening under the mount’s rocky peak, just short of the WA/NT border.

After crossing the border the high sheer bluff of Mt Leisler came into view, jutting proudly above the flat red sands of the surrounding country. As you travel east from here, there are always some great peaks to admire: Mt Leisler in amongst the Kintore Range; to the north-east is the blue-tinged bulk of Central Mt Wedge; directly in your path, like a beacon, is Mt Liebig; and east of Papunya, as you swing south, Haasts Bluff dominates the road. It’s a great drive.

Back at Kintore Range, we stopped at the relatively large Kintore Aboriginal community to get more fuel and check out the store at this well-run and well-established community. Soon after we passed Sandy Blight Junction and another Len Beadell plaque, before taking the diversion to the previously mentioned Willie Rockhole. Farther east again, in among some rocky hills, we found a lid-covered rock hole with faint circular rock engravings (the circles denoting water), a tell-tale sign I was close to it.

We stopped at Liebig Bore for the evening, a major water supply for the nearby Aboriginal outstation of Warren Creek. Desert country dominated the view to the south and the road showed signs of much more traffic between the numerous Aboriginal communities, with corrugations chattering away and abandoned vehicles forlornly scattered along the edge of the road.

East of Papunya you can either continue on to meet with the Tanami Road or swing south towards Glen Helen; we took the latter as it’s a pleasant drive that traces the southern face of the West MacDonnell Ranges and all the gorges and delights it has to offer.

After stopping near the base of Haasts Bluff and paying homage to old Fred Blakeley, whose ashes were scattered over this sacred Aboriginal peak (with the Aboriginal people’s permission, as Fred was highly respected by them), we pushed on and stopped for the evening at the Finke Two Mile. Here, the river, not far from its source, has Mount Sonder (one of the most impressive peaks of the MacDonnell Ranges) as its backdrop. It’s a camp we always enjoy, with the permanent water and green reeds attracting a host of different birds.

Sadly, we were also back on the blacktop and Alice was less than 150km away. Our adventure for this year across the Gary Junction Road was over, and it’s a drive you’ll all enjoy as well.

Travel Planner

WHERE From Marble Bar to Alice Springs is around 1400km, depending on which way you go east of Papunya.

PERMITS To travel the full length of the Gary Junction Road you need a permit from the Central Lands Council in the NT and the Dept of Aboriginal Affairs in WA. Both are available online and are easily applied for and generally quickly issued.

FUEL The longest distance between fuel stops is 400km from Marble Bar to Punmu. Remember the track is sandy and you’ll use more fuel than you do on the blacktop. Punmu is probably the least reliable fuel stop along the way.

Fuel and limited supplies are available from: Punmu ($3/litre); Kunawarritji ($3.40/litre); Kiwirrkurra ($2.50/litre); Kintore ($2.15/litre); Papunya ($2.04/litre). Papunya is open 24 hours, with payment by credit card only.

MORE INFO The Beadell Roads is an excellent guide, which details all of the Len Beadell-made roads including the Gary Junction Road. Available from Westprint Outback Maps.